A pre-publication first look at the short story by Rendell Deni, in the upcoming anthology from our imprint, Ink Tone. Curated by Ash Ari.

For details, join our list. Enjoy? Leave a tip.

1.

I was thirteen in 1995, the first time I decided to die young. Walking out of the warm University Street theater with Luke and his older brother, we’d just seen The Basketball Diaries, and the moon was big and so hopeless. There weren’t a lot of stars in that sky. They were knocked out by all the lights. Shooting stars, now and then, between the clouds.

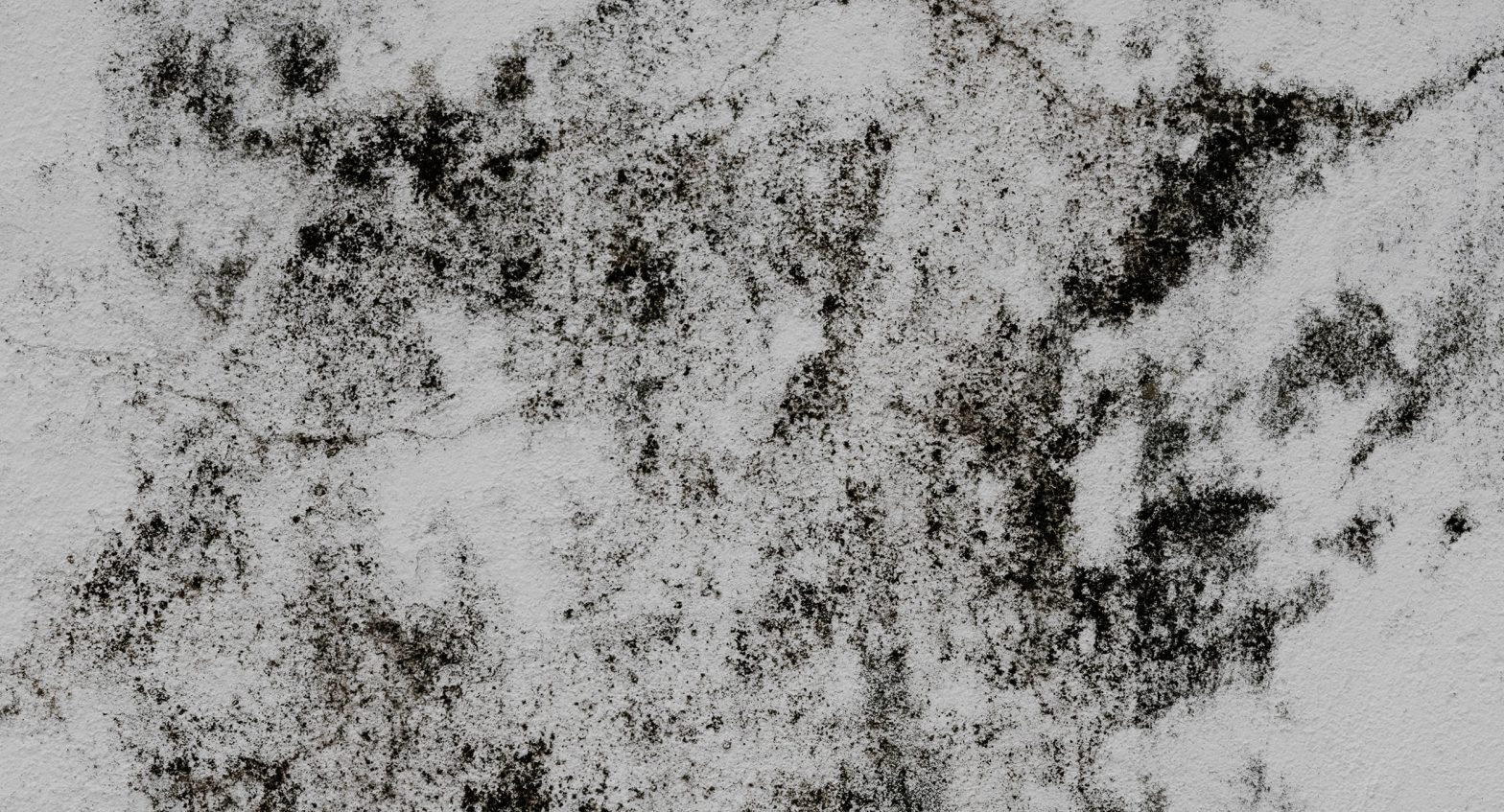

In Dearborn, south of Detroit, things got cold fast on April nights. Bits of ice like dust just kind of hung in the air, coming down so slowly. The asphalt and the cars were all coated in an eighth of an inch of it, untouched since the last show. The kind of wet, cold night that gave you a sloshy shoe print with every step. The concrete walls had bits of dark moss climbing up the fine cracks, from where they met a little runner of ice-tipped grass by the sidewalk. All of this was made darker by the cold.

The oaks were heavy, hissing with leaves above the movie-lot façade of strip mall architecture.

The movie had me thinking about how fucking pretty a suicidal kid can be. Even though I wasn’t anywhere close to understanding that’s what I was thinking exactly.

I was about ready to give it up to Jesus right then and there.

Luke and Dillon were bullshitting in the front seats, and I was watching the trees go by the Volvo window – one of those boxy, blue ones, an ’85 in good shape because their dad was such a tightass about literally everything. Jamming STP’s Purple on the tape deck. Luke pulled a couple of menthols from a pack of his dad’s Newports, handing one back to me.

I lit it with a black Bic, drawing in, rolling the window down a notch, with a little cough. The moon hastened past suburban rooftops, as we flew up Marshall hill toward Wendy’s. Dillon said, “You shouldn’t be taking those, man,” but Luke didn’t answer him.

Can’t un-light a fire.

We went to movies all the time back then, ever since Batman Returns in ’92. Just the three of us, some kind of breakfast club. I remember it clear as day. Dillon was sixteen but we were only ten, these two little shits. And when Pfeiffer put on that catsuit, every young guy in America came, just a little bit – puberty be damned – watching milk spill down her chin. That slack-jawed wonderment was only another face of my innocence, like it or not. Kind of like my death wish.

Anyway, I was talking about the night after Basketball Diaries. This was ’95 and I was thirteen already, minutes later, smoking that cig in the back seat, flicking ashes into the rush of air, lucky if they quite made it out the window. Tipping back my Timberwolves cap. I had just now come to the realization that I was really going to die. Fate was speaking to me, somehow through the moon. Something about DiCaprio seemed to make that alright.

The moon was this big empty, and I was kind of like having a conversation with it, all to myself in the back.

How fucking sad you all are, on that rock, it was saying, I can see all your addictions, your tiny little stupid, meaningless stories that don’t matter. How ridiculously sad are we, I agreed, with our big egos in these little bodies, and the anger, all this rage in our music, and the stars going out because we’re afraid of the damn night? How fucking depressed do we have to be to work our lives away and hate our parents?

The moon was right. I mean what kind of alien smokes cigarettes at thirteen?

Say what you will, most kids are more than capable of understanding every bit of all the myopic sadness in the world, just like most kids whack off far more often than you’re probably comfortable with knowing about. Kids have a better knowledge of the hole in the universe than most adults. Because there is no understanding it, as in knowing why. You can only understand it, like just knowing it. You don’t always have to put a thing into words, and try to trap it, for your clumsy adult mind. Like catching ghosts in a cage, slamming the lock on.

I was feeling like the whole planet is all fucked. Not balling-in-the-backseat kind of fucked, just a quiet-kid-sucking-down-smoke-like-candy kind of fucked. Dillon and Luke were shooting it back and forth still, riffing on the movie like a couple Irish kids in New York. But that’s not who we were. Truth is they were great at knowing the lines, those brothers could recite whole movies or seasons of a show, after seeing them just one time, and I think they actually did a bunch of times, but we were all just terrible at having a damn clue who we actually were.

Dillon was nineteen that night. He pulled a shooter out of his pocket, this one-shot mini of Fireball, and it glinted bright orange under the streetlamp as we tore past, and he pounded it back.

Dearborn’s a bit older than most American suburbs, lots of early-1900s brick colonials with cinderblock foundations, steep rooftops, and these tall, thin oaks everywhere you look. Like five or even ten to a house, green and dark with leaves. The night was coming on snowy now, from tattered clouds. Thick spring fluff, wandering, slow. I saw an owl – I think it must have been an owl, it was just that shape, and we still had them in the neighborhood every once in a while back then – winging across the darkness above the trees.

The area where we grew up was doing fine, even getting some remodels in the 90s, as Detroit kept on falling down in the background, making one long drawn-out death scene out of the architectural background noise of our lives. The oaks made you feel like Detroit was a hundred miles away, even though it was really only about five, and you’d catch skyline now and then through the gaps.

The oak forest is like that. Even filled through with suburban cul-de-sacs, basketball hoops and bicycles and such, even hundreds of years since the oldest grandmother-trees were chopped down and we chased out the Indians, something about Dearborn let you know that we were still the outsiders. Nature was thick even in the city, even in ‘95.

On nights like that it muffled the world. The owl made no sound, owls usually don’t, and then it was gone in the dark.

Oil money ran most of the biggest houses, even as the auto industry was dying. Peak oil was two decades off yet, Riverside and even the counterstrikes were six years out, so this old money town where we grew up was doing alright. As white kids with French blood we weren’t exactly a minority.

My dad was a postman, so he was always going to have work. He used to say he’d be delivering during the rapture.

When too-skinny, too-white, young Leo DiCaprio was masturbating on that New York City rooftop, being Jim Carroll in the movie about his life, beating it for all the world to see – and man that soundtrack took me away with it – I could totally feel him. I mean his heart. Just alone with the night. I think all I ever truly wanted was to be alone with the night like that.

It’s this feeling. Like words and stars are meant for lovers after all. And it kind of made me want to die.

2.

If the world could be so wrong, maybe the best of us were dying for a reason. At sixteen in ‘98 when Mike Starr overdosed, it wasn’t the first time I’d seen an idol go out like a flash. With Kurt Cobain’s suicide I was too young to really get it. When Bradley Nowell flickered out, believe it or not I didn’t even know his name. But by the time Starr died, I was pretty much immune already to the surprise.

Self-destruction was the soundtrack of our lives. I was a sophomore, about to drop out of high school.

That’s what it’s like growing up though. One second you’re this kid who doesn’t know anything, and the next, maybe just two or three years later, you’re some world-weary street poet, high on mushrooms and ready to die for any girl who’ll give you the time. It seemed like forever to you, every class an endless limbo, every desk a desert, a life sentence for being young, let alone the absolute fucking eternity represented by three years. So when everyone else is shocked by that rapid transition out of childhood, you don’t have a fucking clue what they’re all talking about.

Time is relative. But time is also absolute. Mike’s body went undiscovered for two weeks. The overdose wracked his life out quick, it was probably really fucking painful for a minute or an hour, and then for two weeks he just sat there, growing awful, rigid and pale. No shotguns, no conspiracies. Ugly and alone, no shooting star in the end. Dying young is only pretty in movies, though I didn’t know it then.

During those two weeks while he was stiffening, getting right nasty in that chair, way out west in Seattle, I was hanging with Erin in Dearborn. Watching violent movies about kids with their hearts on fire.

Other people mostly sucked. It’s a whole world of fakes and phonies, and by sophomore year that secret was out. Luke’s band was cool for afternoons jamming beer cans in the backyard, but that’s about where our social circle started, and ended.

Which was great on days like these. Her parents worked middle class jobs, and believe it or not nobody from the SS or the prison camp – I mean Hughes High School – even came looking for us. We were the kids nobody noticed somehow.

It was easy to get a bottle of Jack Daniels, Beauchamp’s older sister hooked us up anytime for a small fee – sometimes just a kiss – easier than a dime of weed. But neither was really tough for anyone with connections in the 90s. So we spent our days drinking Jack and Cokes on Erin’s dad’s couch, watching Menace II Society.

I wouldn’t take it back for the world – the sex, the insecurity, the drugs and heavy metal of those days ditching high school.

Erin and I met, on the lip of adolescence in eighth grade, when we were in the same project group during Western Civ. It was kind of a cool assignment, that semester, where we were creating our own futuristic countries, solving problems and that’s part of why we hit it off.

I don’t know if girls really do mature faster than guys, but I can tell you for sure that Erin was ahead of the class. That’s part of why the group didn’t want to listen to her of course. They could barely speak her language.

She was ahead of the teachers, not in knowing so many facts, but in understanding how everything was twisted beneath it all, and how little their facts meant. Instinct, like me, just screamed every day in her heart, like mine.

She dressed like it was Halloween all year, and most people never do look past the way a girl dresses. She was the chick who hit rebel early, goth before goth was cool. Sewed a long, felt demon tail onto her favorite checkered skirt, that she wore with black leggings, and black bra straps showing where the black collar of her white Butthole Surfers t-shirt was too big.

I was still wearing that damn Timberwolves cap like it kept my head on, and Rick’s XL hand-me-down Nickelodeon t-shirts. I’m surprised she noticed me. But it was all about that Western Civ project group. We were the only ones in the room riffing on about the Communist Manifesto. Dillon had shown me the website for the Anarchist Cookbook, and so Erin and I hit it off, and before you know it, we were sharing a cigarette on the walk home from school. Picture the prettiest oak-lined streets, and that’s what Dearborn was on those days in the fall, gold and orange and green, coming home from school. We were a couple of eighth grade American misfits, goth twins in the forest.

Fast then, like time is always racing (you just don’t know it when you’re young) I was sixteen. I was driving my own car, this old Camry, and those pretty, slow walks fell away. Funny how we give up the best shit in life, without thinking twice. I was so eager to grow up. So eager to die young.

Erin dug on cruising with me. She always had somewhere to be. She drew this Sharpie mural on the interior of the Camry, when we were high on mushrooms one summer. Like some kind of tattoo, full of all these lines.

She was fifteen years young, lying back on her parents’ couch and laughing her squirrel laugh at things that were probably more tragic than funny. Yeah, something was wrong with us, but we were beautiful. I was growing out my hair, blond over the open collar of my favorite black flannel.

Her lips were these thin ruby lines, and when she looked up at me on the couch I swear there were literal sparks that burned the air between us.

Funny though I’ll compare her to snow.

Erin was like when the snow was coming down on some perfect afternoon and nobody in the world gave a damn where the two of us were, and we were just watching Jenny Jones on her little bedroom box tv and talking about more beautiful things and the ways the world should be, and ended up laying across her bed from the different angles talking, just talking like two best friends talk, about fucking anything.

It’s hardly a blink in time, looking back. Not that there weren’t endless days. Nobody can count them if they try, when they’re going by.

Or I’d be laying out on her bed and watching her at her pink-framed vanity mirror, and we’d be bullshitting about somebody at school, or the book I wanted to write, or Vanessa that moved to Texas. Or she’d be drawing with her markers on some oversized pad. Listening to Mazzy Star, and her window was done up with those thick curtains that looked like Mazzy Star sounds, all warm but dark, pink but smokey, like a teenage girl alone in a dive bar where they won’t even let her drink, and they matched the walls. And she had this thin string of gold lights up across the wall.

Dillon died in ’97. For him, Alice In Chains went on forever.

The world didn’t bother mourning Luke’s older brother. At twenty-one he put a bullet through his damn head. He owed his supplier all this money and it spiraled up to where, in that little closed-off world we all think is so important, I guess he couldn’t see any way out.

Addiction will do that to you. He was still living at home. Don’t ever underestimate how good felons are at multitasking. Yelling back and forth with his parents about a stolen credit card number – it was all about money – he shut himself in his room. Twenty minutes later there was just this snap of thunder, shook the pictures on the wall and the plates in the kitchen, and Luke’s older brother was gone. Nobody knew he even had a gun in the house.

I couldn’t be there for Luke like I should’ve been. I was kind of living in my own shell back then. Mom always called me Turtle. I ended up at Erin’s on that day.

She was soft, open, intelligent. She was an artist, anyway, a poet like me, and she understood the way feelings and words don’t always match up.

Her pussy was like heaven.

I can only hope Dillon ended up somewhere half as perfect, the only place I ever really felt like I was home. Maybe you don’t get it, maybe it’s just biology. But I don’t think so.

He’s been gone all this time. So, I can make light of it all I want. People are always doing things nobody should be doing, in real life.

Like when we were sitting in my car late at night in front of the house, dreaming about the Jenny Jones sniper, and how hilarious that would be.

What’s crazy about this planet Earth, is that so many things can all be true at the exact same time. While Mike Starr was lying dead in that chair, getting all stiff and starting to decompose like some geriatric, we were a couple thousand miles away, and I was holding her felt devil tail on that couch, leaned over into me while we were watching Menace II Society.

Hell, Starr’s mom was probably doing all sorts of things that week. Hanging sheets out to dry in some beautiful sun, on this clean lawn, all while her son is already dead, and she won’t know it for days. Life’s a horror show, it really is, no need to dress up the dead.

We die. Stars fall. Idols die. Bombs fall. And the world keeps right on turning. The universe is just so busy making sure that all these trillions of things – car accidents and kids’ birthdays and black holes in the epic black of space – are all happening, that it doesn’t seem to really give a shit what they are, whether or not they should be happening at all, or if there’s even any god damn decency to the way it all plays out.

3.

I wish you were here Tom Sawyer, to see it all. The cult of personalities, the mad seasons.

Maybe these long-gone musicians mean nothing to you, but no doubt the train is just getting started. Hell, they were meaningless to me, and to most of the world, even when they were flying high. Egos are helium things, after all. The lucky ones become songs left behind, and even the best of those aren’t going to last, not really.

Photographs fade. Fog dissipates.

At some point we’ve got to find some satisfaction just knowing what we were. Because we’re not here for long. Rich, famous, talented, tainted – time doesn’t care what you think you are. By the time you see your reflection, it is already gone.

The Deadtrain chugged right through, shattering the mirror, cleaving a swath through the world over the years that followed. I picture little River Phoenix at the helm, and Joaquin’s standing there beside him pulling the chain in his Joker getup. I feel like the whole cast of The Explorers is behind them running the car like a misfit steam engine, with Number 5 playing Wesley Crusher, Pink Floyd in the back in black and white, feeding corpses to the engine, shovel full by shovel full. But that’s only going to score with a very few of you. All jokes die in time.

The Deadtrain takes with it every trend, every frivolous argument, every moment in total and complete silence. Every bad movie, gone. Swallowed. Every previous version of you – gone. What’s the difference between the dead and the past, anyway? The cars are sealed up like caskets, thundering into the tunnel of time.

Riverside in ’99 wasn’t exactly a shock to me. Erin and I had talked about similar shit, to be utterly, nakedly honest. Some people wear their misanthrope like a cross. For E and I it was a second skin.

Don’t worry, I’d never advocate random violence. But that particular daydream wasn’t as rare as we’d like to think, for my generation. Everyone that ever heard Jeremy, since 1992, had thought about it. If you think the line between those who daydream and those who do is anything more than split-hair-thin, you’re just not facing it.

Is that the thin line of sanity?

Jeremy was this anthem about a kid who really did shoot himself in his Middle School classroom, in front of thirty other kids, in Texas, in 1991. It was hardly the only anthemic Gen-X reference to guns in schools. But it kicked off a decade, which closed on the shooting at Riverside.

Don’t blame the artists. Leo Dicaprio had the same daydream when I was thirteen, trench coat and all you know. Art imitates life, imitates art, but there is no question here of which is the egg, and which the B-21.

You have to see we were warehoused, by the thousands. We were the victims. The lost children of an asphalt, suburban hellscape, unprecedented in human history. In these giant, blind concrete prisons, for twelve damn years we were told to just wait to live. Without consent. Sure, some were sociopathic enough to come through it all intact. Kudos to the sycophants, the rich kids, the phonies, and those who just didn’t know any better. But don’t act so fucking surprised that a few of us went just a little bit nuts in those asylums, and did what so many others thought was only a wild nightmare of a daydream. Or a movie. Or a song. Don’t pretend like poor kids hadn’t already been shooting each other for decades, over god damn sweat shop Nikes, and you just didn’t care as much.

Say what you will about American empathy, we love the dramatic. Gun control? I was always for it. But let’s talk about self-control, in this generation raised on Kool Aid and apathy.

Bill Clinton was bombing Kosovo with undisclosed drones at the time, setting little black kids on fire for a million dollars apiece, like 50 Cent with a stack of hundred dollar bills, that kind of thing, and nobody batted an eyelash.

Classes went on without missing a beat, every perfect day. The Cranberries sang their heart out. Pop music – U2 – was the pinnacle of our empathy, at the peak of civilization. Crowds were singing, DVDs flying off the shelves. AIDs, Tibet . . . each cause had its own concert. But I promise you nobody was really listening.

I was at HFCC that April, and class broke up right away when Miss Herring broke the news that those white kids were shooting up that white school just a few miles away, past the oaks. We were transfixed for hours at the TV in the cafeteria.

We love tragedy, that much is clear to me, but mostly just when it looks like us. There was this thing happening, culturally, where we were all desensitizing. Think back on the US invasion of Iraq a couple years later, and the way we were all glued to our TVs watching live footage of American tanks literally rolling into the desert, live ammo rattling, satellite-fed cameras, and don’t ever question the desensitization of this population again. Violence, in its proper arena, is bigger than the Superbowl.

You can tell me all you want about the who’s and the why’s, that’s not my point. My point is that violence itself has become such an ubiquitous part of our lexicon that we don’t even have a clue how immersed we are. At a certain point the train became a bullet, a greasy black fireball roaring off the track, smoke billowing over the hills, lightning crackling from its wheels. We’re so afraid to look it in the eye, but its shadow is fucking everywhere.

Y2K shook the foundations of society. For us in Dearborn it wasn’t much at first, muffled by the forest, and the oil money, all those oaks, when the stock market came crashing down. Heck most of us even tried to keep the old calendar for a while. The rot spread, and the wound was showing up worldwide. Even Johnny Mnemonic couldn’t stop it. When the banks started making their own rules, in that end-times fight club – the peak capital economy – I was still too young yet to really understand it.

When the Heaven’s Gate cultists drank their Kool Aid for Space Jesus, owning the Matrix in their own way for the flip of the millennium, I’m sure they thought it was a really big deal. Like those kids in Kosovo thought they were a big deal. Like Pearl Jam, commodifying Jeremy Delle six years before Riverside, thought they were a big deal. Like the kid in the tank with the camera on it thought he was a big deal.

How the world was shocked at all by the time the World Trade Center came crashing down, goes right over my head. Who wasn’t paying attention by that point? Who wasn’t already numb as fuck? How many bombs need to fall before we wake the fuck up to the hailstorm? If you don’t know what it’s like to fear the sound of a bomber roaring overhead, you are one of the lucky ones.

Consequences be damned. Bill Clinton, I know you’ll find it hard to believe, but literally nobody saw him the way you know him, before Y2K. In any case, I was completely unready when the counterstrike hit. I think the whole world was.

Our story is just lines in the cement, in the end, red flowers blooming in the blood, rubble and snow, like they do. I’m not talking about why, I don’t give a fuck about that quagmire of everybody’s god damned opinions. I’m not talking about what should have been.

I’m just pointing out the obvious, that nobody can really deny if they’ve been paying attention, no matter where we go from here. We’ve all lost our god damned minds for this bloody, lovely, hypnotizing violence.

Nobody who matters died, the week of October 11th. But absolute time rushed onward anyway, and don’t kid yourself that fist-full of hundred-dollar bills was still burning, like a wildfire, just off the screen.

If you don’t know the sound of bombers overhead, that fear of the world crashing around you in a thundercrack, a helpless concrete instant, the utter death and blind dismemberment, the disappeared families, the paralyzed, the children of the PTSD – implied by that stupidest English monosyllable “bomb,” you are, in fact, among the lucky ones.

There is no fear in all of fiction to compare with that sound. I pray you hear it, just once.

With all the shit going on in the world, some people react. Erin met this reborn Christian guy, Terry. I called him Terrytoons. I don’t think he even knew what it meant. I was just trying to infantilize the jackass.

The truth is that never in all that time had E and I made anything official about us beyond being friends with benefits, and co-conspirators. She was going her own way. I can see now that I was stuck in the past, like I was still a smoker when she’d gone vegetarian, working out, jogging the park at midnight. Truth is, she left me far behind. She made a couple angular turns around the change of the millennium, but when I’m totally honest I know that Erin was made for better things than me.

In any case I ended up kicking it with the band a lot more often in those years. If you want to know trouble, get a bunch of boys together. It wasn’t all that shocking when Evan got in the motorcycle accident – Danger Dan we called him, the ladies’ man with the good hair and the smooth voice – and it left him kind of retarded. To this day he’s a republican. Hell, so was my dad before he died, and he was smart as anyone, but that was before the coup made cartoons of all that political shit.

Anyway, it was me that took up the mic in Evan’s place.

I wanted to be Roots Bloody Roots, but my range was naturally more Facelift. I’m not trying to say I was ever as good as any of the best, but those were the influences, toss in a little Smells Like Children and stir vigorously. And I had my moments. The best of grunge and metal, to me, always has a touch of the blues, especially in the vocals, and I rocked that lower register. Luke was a lot more experimental with his guitar, but I played rhythm. I had a blast with the goth makeup, for a few years anyway, and we made melodic, In Flames-influenced metal to die for.

Crazy, the way it changes your mind when you give birth to a thing. Kids fuck up your brain, is what it comes down to. When you become a parent that is the exact moment when you stop being trustworthy or having a clue what’s what. A billion years of genetics step in to make sure you can’t see a damn thing straight. If you could, you’d never make it.

That particular blindness is there to save us. You know it’s the god’s honest truth. Thank god for the blind, stupid love of good parents, where they are, anyway.

Songs count too, like poems or paintings, anything with a voice. Those riffs were our babies, and we couldn’t stop staring at them, sometimes.

We did this cover of Pearl Jam’s Black. We made it into an industrial banger, dark like a tattoo, but the chords were the same. We gave that one, unassuming 90s b-side that it was, this much darker, NWO kind of vibe, and the little crowds around Detroit ate it up. Probably heard by about a hundred people, total, ever, which was honestly just how that should be.

The programmed drum part was very Reznor, with just a little funk in the bass to compliment it, all sass the way he used to do it on Pretty Hate Machine, before he died on that cross.

Anyway, these absolutely perfect moments have happened around the dirt-hole cities of America for decades, with little groups gathered around little stages, where nobody knows and nobody fucking matters. It’d kill you to know. Nobody recording. The most beautiful things leave no trace. Distant stars burst in cosmic radiance because of local musicians on small stages, when they hit the melody just right.

I killed the chorus on Black, and it felt like I really was letting some kind of demon out, some nights, to play.

We were high, most of the time for gigs. Like it’s funny you get a chance to shine your light for this inconsequential, drunk audience, and so it’s only natural you’d want to get right fucked up outside the gig. Sometimes hammering back a few drinks, but most of the time it was about sharing a joint prior, and then just being high on the music.

Being high on a moment.

Like what is that light? Every musician since the dawn of time knows what I’m talking about. I don’t know how it stays a secret – they don’t even talk about it in art school. You can see it, I god damn know you can. Metalheads and opera fans are chasing the same light. Tribal drums and tortured guitars. Inspiration – giving it up for Jesus, you know.

The thing about Luke is, he had every reason to be depressed. So you can’t hold it against him, all that darkness in his blood. It’s just what the world was made of.

We were the last generation that really got to enjoy cigarettes. The artists, the goth kids, those of us wearing all this black. The 90s musicians. Ever seen a magician with a cigarette? Now, a comedian could pull it off.

Imagine Jesus with a cigarette.

But did the man ever tell a joke?

Lucas, now Luke was a unique case. He felt the general absurdity of life, when we were thirteen, don’t doubt it. Luke was bisexual before it was cool. Like when it was the sort of thing that could get you killed, in parts of the world. When we were only ten years old in the US of A, he had to deal with hazing about taking dick, because they said he walked like a girl. I remember this one kid always threatening to give it to him, as if he wasn’t a virgin, as if that wouldn’t have made that guy gay, as if Luke wasn’t about the nicest guy you could meet. He was absolutely a virgin, sensitive and alone, and they were all fucking him up. About who he thought was hot, when that circle-jerk story got out – as if he didn’t love Catwoman’s pop culture cumshot at first sight like every good fucking little red-blooded American boy was supposed to do.

At nineteen they’d let us into the bars to play, but only serve us coke. Zach was twenty-two, so that was the ticket, to get us into the underground metal scene in post-Y2K Detroit. Clinton was Caesar, sure, but life went on.

Didn’t stop the whole four of us from doing a shot before the show on that October 11th, in the great, brown, monster conversion van we used for equipment transport. We’d smoke a blunt between sets, outside, and that was still almost twenty years before the eventual end of weed prohibition. People getting thrown in the slammer like puffs of philosophy in cages, back then.

I know it’s hard to believe, but that’s what people were worried about back then, right before the mass extinctions. Who was smoking what, and who was fucking who, and whether it was all illegal.

If you were going to bring any sort of an audience to a Detroit bar in those days, they’d bend the rules for you and look the other way. Cops had other things on their mind, besides what the white kids were doing with their marijuana cigarettes.

The bar I’m talking about right now was Telltale’s, on Ivy. Luke was smoking a cigarette on stage, and little bits of ash were sputtering out into the air as he finger-picked his way through the solo. The light was behind him, and I remember these big rays cutting out his edges in silhouette for me when I looked his way. His hair was spiked and dyed black.

Luke’s aunt died in ’97, of a heart attack the first time she watched Titanic. They had this complex relationship. He was kind of in love with her, I think, to be honest. Can’t blame him, lady exuded cool, had a nose ring, finger tattoos. She was the one that got him and Dillon both into punk rock when they were kids, and vinyl, and a little bit of Celine Dion, and she was the one that bought him his first guitar.

By the time we were on the stage at Telltale’s, he’d upgraded to a suite of axes that would make most teenagers jealous. The one in his hands that night was this sexy blue-fade Jackson X, that he had stickered-up like a beast. That’s what you had to do, sticker it up. The Violent Femmes, Rage Against the Machine, Che Guevara.

His eyes were shadowed, from eyeliner and the kind of amateur lighting rig you get in those little clubs. Torn up jeans, no shirt on his gaunt, Bowie-esque frame. It was his hands, in that moment, that drew your attention. The whole place was focused on his awesome hands. Hands are underrated, especially musicians’ hands, as the seat of life.

Say what you will about eyes, the poets are missing a million words about what it’s like to just watch a pair of soulful hands at work.

Sweat makes a body shine. I doubt Luke had eaten anything since lunch that night. He had a bit of an extreme view on veganism by that time. And maybe a bit of an eating disorder. But the guy was a brilliant guitarist. If brilliant people were normal, well they wouldn’t shine so fucking hard now, would they?

Watching his fingers glide on the strings, pressing down where each note lived, so as to coax it forth like some vocal summoning, from a machine with a soul that evolution in all its cruelty never gave the power of speech, I was, like our little audience, bathed in the light of what he was saying.

If you think words are a poor trap for feelings, try using them to describe a song. Music is where heart speaks to heart, without a middleman. Yet with all the complexity of life.

That melodic solo was like what a robot might say about indifference, after it was given a beating heart by some alien sun, and for the first time it could sense the raw nebula space-stuff of what it’s like to feel all this undirected aching inside.

So as he leaned his head back, ashes dropping to the stained carpets of the stage, closing his eyes, dark sweat dripping down his long cheeks with mascara, it took me too long to realize anything was actually wrong.

He hit the stage accompanied by a big silence, the air in the dive sucking in, like a sudden breath after the droning thunder of that solo section. A rough edit as the programmed drums went forward a few beats, and cut out with an ugly whine.

I was closest to him. Luke was out like a smothered flame, but breathing. I pulled the X away from him, strap over his head, holding the back of his head, all in one motion, high as a kite, saying his name.

4.

For a culture that worships sex and violence, it’s crazy how rarely we look them in the face. We’re dancers at the fire, but we never take off our masks.

I came into the world the same month Randy Rhoads’ plane crashed, in October of 1982, just a few weeks prior to Halloween. I’ve always been a little bit scared of flying, and in love with guitars.

I played a bit now and then, over the years. Mom bought us piano lessons for a while when we were growing up, we were that kind of middle-class family in the 80s. She could afford the lessons, but there was nowhere for a piano in our crowded house. I was never very good. When I picked up a guitar though, things happened. Still, somehow I didn’t play much at all, until after Luke took that fall.

Rhoads was cremated, or what they retrieved from the plane anyhow, like my dad after his heart attack. Ozzy Osbourne threw his ashes over Niagara Falls. My brother Rick and I put dad to rest in the water near Camp Lake, outside Sparta, Michigan, twenty years later. We were the only ones there in those woods that day, besides the brown owl that scattered, seen for just a second through the branches like a woodland spirit. And I’m sure I said something into the breeze on Dad’s account, a heartfelt prayer in the moment, but I couldn’t tell you what it was, now.

Our band went by The Fall in that next incarnation. Lead guitar and songwriting fell into my hands. I was never a shredder like Luke, but I could solo. I could groove. He was the one that should’ve shared October with Randy Rhoads.

We had a cool logo done up by a groupie from our high school, this badass artist girl who’d been in the circle of the band for like ten years at that point. It went on our show posters, on garage band sites online.

Our biggest original track was this metal ballad I wrote, with that heavy freakout in the middle ripped off from Pantera’s No Love, and lyrics that riffed on Creep and Planet Caravan. If we were creeping anywhere it was toward the mainstream, grunge and rock, in those years. Our most popular cover was Sad But True, by Metallica, which we did faithfully.

But if you want to know my favorite? We gave this clear-toned, incandescent spin to Without You I’m Nothing by Placebo. To die for.

A couple of our most memorable shows were in the living room at Evan’s ex’s house, at those Halloween parties she threw.

She put on a costume contest, where everyone voted on the hottest, scariest, and funniest costumes all night, and then these cheap prizes, like a slick new copy of The Lord of the Rings in single-volume, or a chrome butt-plug with a sexy squirrel tail. Around one or two in the morning.

She had a normal, mid-size house, inherited from her parents, who died when she was nineteen, in a pileup on I-96. Decorated nothing too crazy, mostly just cobwebs and blacklights, these disembodied hands on the snack table, one bedroom with zombies, and people making out, doing lines in the basement. Never totally out of control, but the PA was loud, and the gigs were pretty much legendary.

Every clique, in every town, thinks they have these important characters, these parties that nobody’s going to forget, but none of it’s true. Just egos, just fog, all these lies we tell ourselves. Big or small we’re all irrelevant, overplayed, passing like snowflakes on autumn nights.

So watch the ones in the corners.

In the backyard they had a bonfire, with this big fake plane tail stood up in the center, wreckage with a shadow like a sword. Cosplay duels, one girl dressed like a pirate. I remember watching Guy Fawkes just owning Kilik, like they were sparring hard with sword and staff, while I was outside, having a smoke and being generally quiet like I would be, in between sets.

When we were playing In The Flesh (our cover of Pink Floyd’s track, with an original moog synth wah-wah outro you’d love), that night it was just before the end of our second set, and I was dressed in a gender-bending Twisted Sister, 80s jean jacket kind of way – black fingernails, eye shadow and a long pink and blue wig. I was watching Evan’s ex basically the whole time, who was making out with Ray Liota over by Michael Myers, who didn’t talk to anybody all night, just always in the background where you didn’t expect to see him, standing there kind of jarring. Holding his hatchet, which looked like it was probably a real blade. A parade of dead celebrities hung around, anywhere you looked.

She had two kids living there, and they were up late, high on candy at midnight. Mostly they stuck together, navigating through all the weirdos and giants, but they were old enough to make a path when they needed one, and everyone kind of watched out for them. But both girls were just hanging near the PA system then, these two Syrian-American 9-year-olds dressed up as NSync, one of them holding a lighter in the air.

Made me smile, looking out on the room. Their mom knew how to throw down, that’s for sure. See most parties don’t go like the movies. Surely you know. But she went all out for these. The projector was playing Batman Returns on the wall behind us, and nobody was really dancing, it’s not really a dance kind of tune, but the room was pretty packed, and people were eating it up. The place opened out the back, past her dining, onto a deck and large yard, thick grass running off fast downhill. Oaks were these giant spears of darkness, with bonfire reflections in the lower branches, and some purple light was putting an aura on the folks outside on the deck, smoking, in my view from the living room stage. Jester, Blade and Hyde. A skeleton priestess in a trench coat, with this twisting black staff, horned skull on the tip.

Evan’s ex wore a sexy Wednesday Addams, hair in thin, long braids, and if you knew her she had these heart-shaped cheekbones, this Arabian goddess look, on a normal day. She’d been a single mom for years, but was doing alright, had a college degree in poli-sci and a family inheritance. Killer taste in music.

And she always loved younger guys.

And she was into that old Ray Liota, no doubt, with his fake white beard, but she was watching me, watching her. Like I only caught her actual eye once, but that’s all it took. Our last song that night was Nine Inch Nails’ Dead Souls, with that popping bass line, and the room was sweating, dancing for that one. The Crow was there, off and on, coming and going from the outside, and I could swear that guy was Brandon Fucking Lee, grown a bit taller.

Before the end of the night it started snowing. Halloween, believe it or not, is a celebration of life.

You might expect me to launch into a bit here about how commodified our culture had become, in those end times. How every single thing we wore was licensed, how often we let all that stand in for character, because we lacked any sense of real identity, becoming this prefabricated nightmare of echoes and wannabes, copyrighted wardrobes, even the cool ones, really, never speaking just reciting lines . . . but I’m going to hold off.

Because Halloween was the night we put on the dead, to pretend like everything was alright. Halloween was the distillation of everything wrong, our most blatant of ceremonies for darkness, commodification and caricature worn as a second skin, dropping all pretense and sublimating ourselves gleefully to the violence and absurdity of this wasteland un-life that had us each by the neck. And, somehow, it was just as well our most innocent. Making a trick of the devil, making fun out of blood and pain, making sexy schoolgirls out of all that unnamable violence.

Karaoke, like I was saying, went on until around one in the morning, and all sorts of these people sang, but it wasn’t average bar shit. If you want to elevate a singalong, get those folks in costume. From behind a mask, you’d be surprised just how many people can really sing.

Anyway, I was sharing a smoke on the deck with this girl Hurley I knew from college, shooting the shit about her wife and kid. She had short brown hair and a markered-on ‘stache, dressed up as a famous 80s porn star. She kept touching people with her hilariously big, floppy dick.

Evan’s ex took the mic. I could see her just fine, past the hovering snowflakes, through the faint breath of the open glass door, across the crowd in the living room where the PA system was set up.

Her track was Rev 22:20, this slow, sexy nightclub, blues crooner. You probably never heard it. This B-side from the end times. It’s got these sublimely subversive lyrics about selling your soul for love.

She had that slight gap between her teeth in front, the way sometimes crooked teeth actually make a person more beautiful, and she saw me, through the crowd and snow, in the aura of purple firelight. She did the song in this zombie, gypsy vibe, with real low lows and a croon that probably made everybody there wet themselves just a little bit, if they were paying attention. In her Wednesday Addams tights with those little black bows, honey-brown eyes, long black braids and all that.

You might know the story of Christopher Reeve’s turn at fate. The short take goes something like this. Born heir to a rich family, movie star by twenty-six, Superman for a decade to the world, with that honest kind of smile. Paralyzed by a horse. He died that month, just a few weeks prior to Halloween.

Good looking guy, that Reeve. Even when he couldn’t move below his Adam’s apple, couldn’t breathe on his own, had this mechanical respirator for most of the rest of his life – people around the world called him a superhero. I think he was still somebody’s dad, believe it or not, so they were probably right.

I don’t know, maybe where you live they’ve totally forgotten him already, as likely as not anyhow, so that’s the gist of it.

And that’s the only way to get what Luke was doing, coming over near the bonfire, in his electric wheelchair bouncing along the turf, his hair tussled and black, with a single S-shaped lock dangling down his forehead. His outfit was basic, business casual. The kind of thing a rich cripple would wear.

I felt a shiver, watching him roll up across the grass. A teenage girl was following him, at the side, a cute bob and not in costume, unless she was trying to be Katie Holmes or something, clearly too young to be at that particular party otherwise. Probably fifteen. She was watching the wheelchair, which cut fast and rough across the grass, with the uncoordinated weight of his plump hand, which was just kind of laying across the joystick. Luke was drunk. He saw me right away. Saw me see him.

Which should’ve been ok. But we hadn’t actually looked each other in the eye in over a year then, to be honest. And I’ll just come out and say it, I was uncomfortable as fuck, just seeing him like that.

I was never an asshole. I’ve always been more empathic than most anybody. Special needs kids were always coming over to me growing up, in school, and I think it was just because I always treated them as human, you know? I mean they fucking are, right?

But this was Lucas. And I’ll be straight, there was something in his eyes from the start that night. Snow coming down all around, in the dancing shadows of the roaring firelight.

I’m going to spare you pretending like I remember everything that was said. The conversation was kind of awkward, at first, and the words wouldn’t convey that anyway. It was strained, is the thing, and after the first, I was afraid to look at him. The girl was taking care of him, holding his drink, holding his vape. She seemed tuned out, no doubt just overstimulated by the cast of oddballs and monsters around the fire. Hurley and an Indian were passing the blunt, on the other side of the crackling, fluttering ghosts and smoke, curling still around that tailpiece that somehow wasn’t burning, kept in this makeshift brick pit. Michael Myers was standing over there, kind of off by himself near the bushes.

Quiet passed at one point between us, just the sound of Luke’s mechanical respirator wheezing, as the whole group around the blaze took a collective breath. And then Luke said, with a tired kind of halt in his voice, “You fucking bastard.”

That’s the only line worth repeating from our conversation that night. It didn’t connect to the bullshit that came before. I didn’t answer it.

The conversation kind of dipped after that, but we were all pretty fucked up at that point.

The shadows were licking the snowflakes out of the air, and the oaks were skeletal titans, scraping the sky, patchy with leaves yet to fall.

5.

You’ll have to understand, we’d known each other since 1993, fifth grade at Rudyard Kipling, and a person really doesn’t have to say much, when you have that kind of history together.

Did you know that Detroit was the richest city in the world in the 1950s? This was the kind of boomtown known around the whole fucking planet, not just for its size but for the richest of the richest calling it home. Like Tokyo, New York, Paris or LA, there was Detroit. Even back then it had its slums, organized crime, union towns. But if you could imagine the curves and lights of 1920s architecture, given a 50s makeover with fedoras and Cadillacs, neon signs and swing skirts, the operatic theaters on Woodward Avenue playing Arthur Miller, you’d see how the grease-stained alleys of a city like that have their own royal, rarified air. Even a bum might catch a glimpse of Marilyn or Astaire, passing through Detroit for a premier, on a snowy night in 1960.

Walking the streets of Dearborn, on that cold October end times night, with my jean jacket open to the icy breeze and my wig flared behind my head like some purple torch. Crossing the main drags the view opened up and you could see the looming skyscrapers of the city, just a few miles away.

Or what remained of them.

There is no fear in all of fiction to compare with that sound.

We didn’t get it as bad as DC, or some of the seaboard, no doubt. A million Americans died in the first counterstrikes alone. But the thing was that the bombs raining over the following years coincided with Detroit’s already steady decline, and where the damage was done, nobody repaired it. Hell, you couldn’t use a cell phone within a thousand yards of the White House after Y2K. The world was shook by that little backpack nuke, that infrared RC monster truck. It was the kind of thing that only happens once.

But the meteoric rise and slow, inconsequential breaking of this almost-capitol, this rich man’s haven, this last cry of the foreclosed American dream – the life without consequence – the Motor City after ‘99 was a much more appropriate metaphor for the great American experiment, than that wannabe plantation, Billy’s Fort as they called it, though it looked as White as ever behind those walls, in the end.

On a night like that Halloween, Detroit was mostly just these skyscraper shadows, that to this day, years later, had no power, black water, no plan, and no official residents. You couldn’t see the rubble in the dark, from this distance, or the refugees who called those crumbling apartments home, the broken windows and the silhouettes of people burned into the brick walls. Just these huge, dark, tall, jagged shadows in the distance. Night on night.

We get what we deserve, sometimes.

I pray you hear it, just once.

A car, just now and then, passed me on the oak-lined streets, headlights blazing. No pedestrians, nobody out trick or treating at three in the morning. Just drunk-ass me in my burnout jean jacket, the slow-mo snow, and that big moon crowning out from the clouds.

Plot is the enemy of any good story.

If there is a villain, if there is a hero, if there is a chain of cause and effect, where everything you need to know is there, boom boom boom – if the destination, any destination, is predetermined, well it’s a good god damned lie.

We all love a fable now and then, don’t get it twisted, I’m not knocking it in that sense. Escape when you need to escape, lie to yourself all you want, it’s great, but I just always think it’s funny. It’s distracting. This fake storytelling used to be the stuff of bedtime picture books, but these days it’s the manual for everything from movies to games to best sellers. And not only does it cheapen everything that could happen in good movies – the stakes, the character, the suspense – it also trains us to be really bad at living.

Don’t expect resolution in life. Don’t expect the good guys to win. Hell, don’t expect there to be any fucking good guys. Don’t expect anyone to explain it all to you before the end.

Life is this endless reel of events. Like somebody left a camera rolling, at the wrong angle, at the wrong time. Characters you love just up and disappear on you. Justice doesn’t get served. And when it does, it doesn’t fix a damn thing. Don’t expect return fire to miss the characters you love.

Everyone on the battlefield mourns.

So much of old age is really just a buildup of scar tissue. Don’t expect to get what you deserve. Meanwhile there are all these things we love to see played out on the screen every night, the fantasies of where we wish we were.

Truth is, we wish there were zombies. We wish there were monsters. We’re generally really eager for a war. Somebody to amputate. We desperately need a world with villains, with identifiable horrors. Broken bones. We need fear to have a form. Individuality. We need murderers. Or why would we fantasize so much about them? We wish there was a rapture. We wish Christ was a killer.

We wish there was anything, god damn anything at all, worthy of remembering as it truly was. Instead, we get this, this trap. If reality is just this endless web, but no spider, life after death after life after death, then meaning is an effervescence, gone before you could ever really grasp it.

We want the lie to define us.

Like when the singer for Nazareth, Dan McCafferty, got nailed to that cross for telling everyone about how much love hurts.

And that train of forgotten time just keeps on rumbling, every day another car, shut tight. Eddie Van Halen screaming at the window, breaking the wires from his mouth, a needle dangling in his tied-off arm, a guitar pick welded to his bionic hand, shredding the strings on his Frankenstein Strat with the fury of a mechanized hell.

I was going to vote for Obama the first time he ran, not that it really mattered. Everyone knew it was a fake election, after the crypto leaks. What should I have done, voted for Jeb Fucking Bush? What I wouldn’t give for another garden-variety phony. These violence addicts were a breed apart. You couldn’t see their tentacles behind the podium. You couldn’t see their drones against the sunlight.

Nobody was pretending Bill was stepping down, they just held those fake elections to keep people from rioting.

The false flags, the friendly fire. The who was fucking who, who was buying who. Everything was public knowledge after the cryptographic leaks, but who really had the time to care? Life doesn’t wait.

And the public crucifixions? Were really not all that surprising, in the end.

Billions of people were still alive, every day. Detroit had been failing in real time for decades. The oil and auto execs – like Phillip and Morris, went B and P. When they were flying high, they didn’t exactly work through the angles on their long game.

A place like Dearborn, which had held out, as a little island of suburban normality, weathering half a century of corporate irresponsibility, was a haven for executive wealth, outdoor security cameras.

When the calendars failed, and nobody knew what day it was anymore, after the fluoride ran out, the quarantines hit, that flesh-eating virus swept through, the extinctions started ticking. After all of this and all of the stuff I don’t have time to talk about, billions of people were still alive.

I’ll never forget seeing Layne Staley live at Red Rocks that year with Mad Season. Moaning River of Deceit, then belting out Would? – like a cursed second coming. Then Primus took the stage.

But I digress. I suppose I just don’t really want to say what I came to say. Sorry about the lies. I promise you every one of them is just an imperfect truth.

That’s what people do, to avoid facing our lives. We come up with all these plots, all the jobs and dates and holidays, the growing up. Every single coming of age story you ever saw was bullshit, you know, even the good ones. Especially the good ones. Because there isn’t an adult on Earth who has their damn head on straight.

This list of names of people we don’t even know – we all have one. Roy Orbison, Hellen Keller, Atticus Finch, Pennywise. Do you know them? I mean do people remember them, in your time?

Peter Steele, Phil Anselmo when that guy just climbed the stage and shot him, dead straight, in the middle of that last Pantera pit.

Max Cavalera. Pius XIII. Kerry King. Strip the names and the lies from the history books and you’ll see pretty quickly how short they are, how little we actually kept of the past.

How easily it could’ve gone another way.

Our absolute time disagrees. The gray absurdity is very certain of itself, in the end. Can you see? The truth? But you’ve got to give us a hand for all that kicking and screaming.

Having the truth is like having ticks.

When I was walking home on that Halloween night, the gray had me tight, and kicking and screaming is exactly what my soul was doing, though you might not have known it to see me. Unless you got right up and looked in my eyes.

We need fear to have a form.

We’re not ready. We’re never ready.

Things were lapsing, repeating, swirling around each other in my head. That’s how I remember it. It was that kind of a drunken walk, where you only remember bits and pieces the next day, and even those are all confused.

Like the traffic light at Marshall and University. I remember looking up at those long yellow metal boxes, hung down the wires, swaying in the wind that picked up just then, as the storm increased and ice was gathering in the down-swept curves of the metal, and on my clothes. I stood there for a bit, not quite sure where I was, even though my childhood home was only a few blocks away.

When Mazzy Star died earlier that year – I mean Grace Sandoval of course, nobody named Mazzy Star ever lived anyway – well when she jumped from that bridge after hearing about Heath Ledger’s third marriage and Robin Williams’ suicide, I had thought I couldn’t be far behind.

Looking up through the snow, past the traffic lights and clouds at that big harvest moon over Dearborn, I could hear her singing So Tonight That I Might See.

I don’t know where it came from, but I’m pretty sure that part really did happen, anyway. Maybe somebody was driving by with the windows down and it was on their Pandora. But for me it seemed like the snowflakes were wind chimes, and the universe itself was whispering the melody.

See Jim Carroll lied to me. I don’t want to sound ungrateful. I mean you shouldn’t generally disrespect the dead, and at this point he’s long gone too. Heart attack, just like Mazzy before she hit the road, just like dad, Luke’s Aunt, just like Randy Rhoads.

I was never going to die young.

I was never going to self-destruct. No matter how much I disused my life, ignored it, fed it all full of dead things that never had a chance . . . No matter what, my fate was sealed.

Like Lucas.

Like Dillon.

Like all those people who died, and all the ones still alive. Even the ones I lied about.

God damn I want a cigarette. Something to calm the violence of my imagination.

Somebody should’ve told me when I was young, I couldn’t kill myself if I tried.

Life is long. Jim Carroll lived until he was sixty, when that heart attack snuck up on him. That guy and his fucking basketball. Riverside was his fantasy, not mine. His heroin dreams spun my world, and he didn’t even have the decency to die for them.

Sixty years is twenty thousand days, give or take. Every one of them too short to get anything done, and too long to excuse your responsibility for failing to do so. Every one of them, filled to the fucking lid with emptiness.

The waiting, that’s the hardest part.

Leo too, you know, he’s probably still alive too, no matter exactly when you read this. Somebody had to take the wheel when Bill Clinton’s long-dead reanimated cyber-corpse finally wheezed its final breath. Joaquin’s too busy manning the horn.

Erin never came back to me, but I’ve seen her a few times since.

For her I think it was a strange vacation, sitting back in the seat in my car after midnight, her foot up on the open window like a teenager who didn’t give a shit, couldn’t be sold a shit.

For Erin, when she saw me it was some kind of deep exhale that her soul totally needed. She was successful, but that never really fed her, like I could.

When we were teenagers I remember sitting with her just like that in my old Camry, and all the lights were off in the house and we were tripping on mushrooms. I remember her sitting like that with one leg up and I was smoking cigarettes and just watching the curve of her calf in the half-light of the Michigan moon. She was drawing with a sharpie on the roof of the car, just these doodles like neither one of us could’ve been paid to give a shit. The underside of that roof looked like a tattoo tapestry, dark with all these tribals, all these little souls trapped in space . . . all these lines. Like words and stars were meant for lovers after all.

The oak tree in my parents’ yard was a twisting silhouette, in the darkness, and I could swear I saw it breathing, all the while, while I was trying to figure out what to say.

Copyright 2023 Arch & Gravity Publishing