Rating: 9

We are one life reaching out into a dark future. We are one blood.

The Lady Jessica

A Spoiler-Free Preview of Dune, Dune Messiah,

Children of Dune, and God Emperor of Dune

*Full Reviews for each book follow down below*

To see the future – to know tomorrow like we know the past. . . What is time, anyway, that it hangs forever ahead, heavy like a stormfront, with all of our hopes and fears, yet invisible? To our senses, the horizon of a moment is so impenetrable, but everything hinges on its blooming.

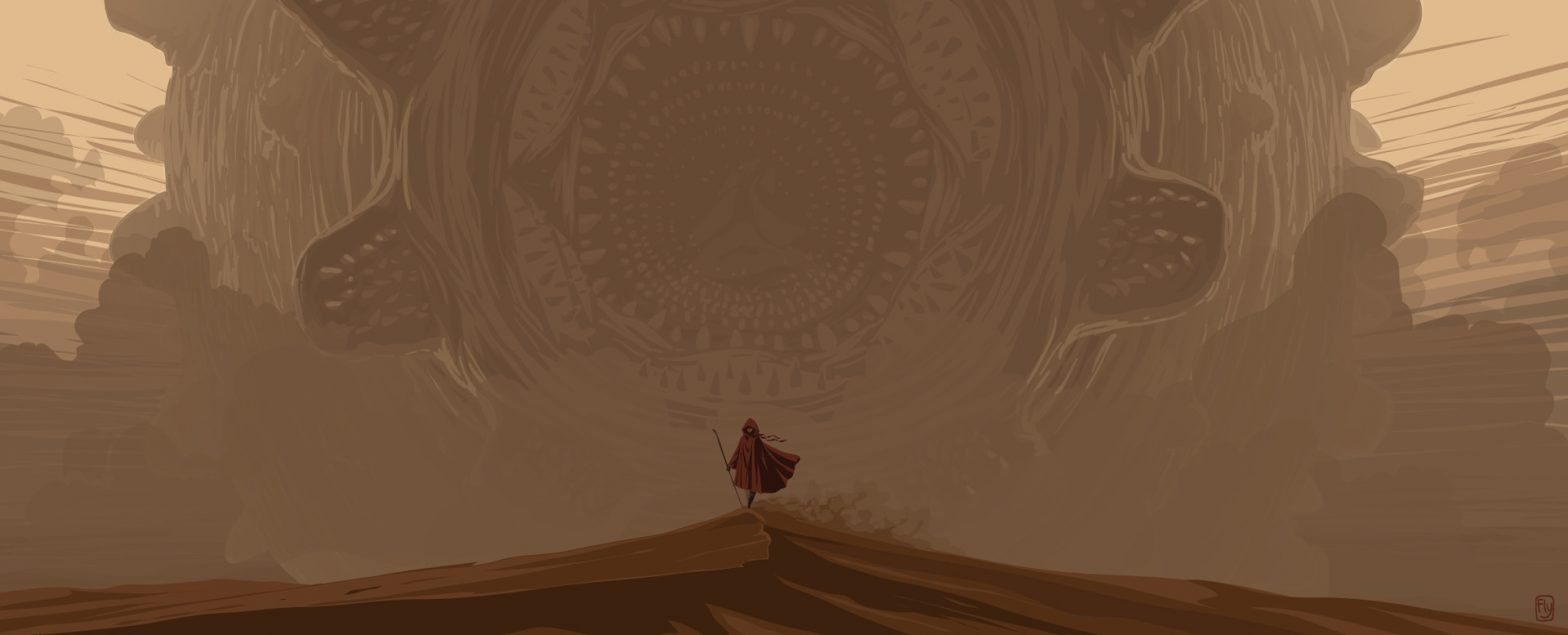

What if time were like a desert, a landscape of waves within waves, dry and deadly in perfect symmetry? We would be thirsty travelers yet, with the one goal, and it alone: to crest the next dune.

This need to know time – the explorer’s credo and Cassandra’s curse – may be the central pillar in all science fiction. Both Wells and Asimov dealt with it directly in their original works, and if they are granddaddies of the genre, there is still room at the head of the table for a father of space operas. That chair is owned unequivocally by Frank Herbert. Like Tolkein to high fantasy, Herbert was not the first to tell a tale of intergalactic imperial conflict and destiny, but the thousands of pages he left us are unique and pivotal, a guiding star of character, philosophy and drama like nothing before.

The short take? If you haven’t read Dune, there is no better time than now. Prepare yourself for an epic, told by a deep thinker and science lover with a true poet’s heart. Dune’s so long that you’ll probably still have more to read years from now. If it starts a little bit dry, you may just remember that it is, at core, a story about a desert. Rest assured that Herbert grew with every page, revealing eventually a tale thousands of years long, lush with so much detail that you’ll want to read it more than once. If you get a collector’s edition, skip the forewords until after you’re done, they’re full of spoilers.

It’s easy to say it never reaches quite the perfection of a Lord of the Rings, but past its flaws the Dune saga runs so deep. This is no common allegory, with easily defined good and evil. There are no light and dark sides, no clear-cut choices. Herbert gives us the deep dive into a philosophy of leadership, religion and human motivations that would leave Sauron needing water wings. Against this long sunrise of tragedy, genealogy and prophecy, a paper villain like Vader might merely evaporate, like so much sand in the wind of an atomic cloud – a childish illusion, a story that could at best be described as an echo of much greater imaginings.

23 publishers rejected Dune in manuscript form, and a fan has to hope some of those editors are still alive today, to experience blushing humility like they should. It’s only sad that Herbert himself is not. He lived to see a following spring up around his work with rare equal, but died in 1986, two years after the awful David Lynch film adaptation, and three after Return of the Jedi rounded out the then-best-selling sci-fi movie series of all time – a story of a spice runner, a messiah from a desert planet who could stop a man with a word, his powerful sister Leah and a patriarchal reveal that would shock the world (or at least drop every 8-year-old movie fan’s jaw for a second, between popcorn pops).

With Dennis Villeneuve’s big budget movie adaptation for Dune on the way this year, I decided it was finally time to tackle reading and reviewing this seminal work. I had no idea what I was in for.

Read Dune (1965), and learn the story of Paul Atreides, his parents the Duke Leto and Lady Jessica the concubine, the planet Arrakis, its deserts and giant sandworms, the mysterious Fremen, the spice melange, the dangerous House Harkonnen and the Padishah Emperor of the Universe. Divided into three sub-books to chronicle Paul’s fundamental transformation, exploring themes of prophecy and revolution, Dune is clearly the work of an obsessive genius, every detail polished and thought through. Like the mentats he creates, Herbert’s writing in this first book could well be thought the work of a human computer. The far future humanity he describes is smarter than we are, more advanced and cunning, developed beyond anything we would even describe as technology itself. Their plans within plans are like wheels within wheels, and Dune feels like the work of a clockmaker, precise and airtight. At heart, book 1 is a hero’s journey. Full of alien landscapes, ‘thopter flights, crysknife fights and royal intrigue, if it’s like anything else you’ve read, well that’s likely because they were copying Dune. While its flaws may fall short of true prescience, as a work of fiction Dune will make you think, make you feel, and absolutely succeed at making you forget for a little while that you’re here, just reading a book, on Earth.

Your truthfulness, that’s what’s dangerous.

Alia to Hayt

Stop there, however, and you’ll be wasting quite the ticket. Dune Messiah and Children of Dune came out in 1969 and 1976 respectively, fulfilling the original saga of Paul Atreides and his family with hundreds of pages of galactic jihad, assassination plots, clones, new generations, ancestral memories and Bene Gesserit witches. What the sequels may lack in measured, honed coherence, they more than make up for with story and imagination. The adept reader will be hard pressed to miss the transformation in Herbert himself as the philosophy deepens, the poetry climbs, and the plots become ever more gray and serpentine, yet somehow breaking free from their own weight – like a phoenix.

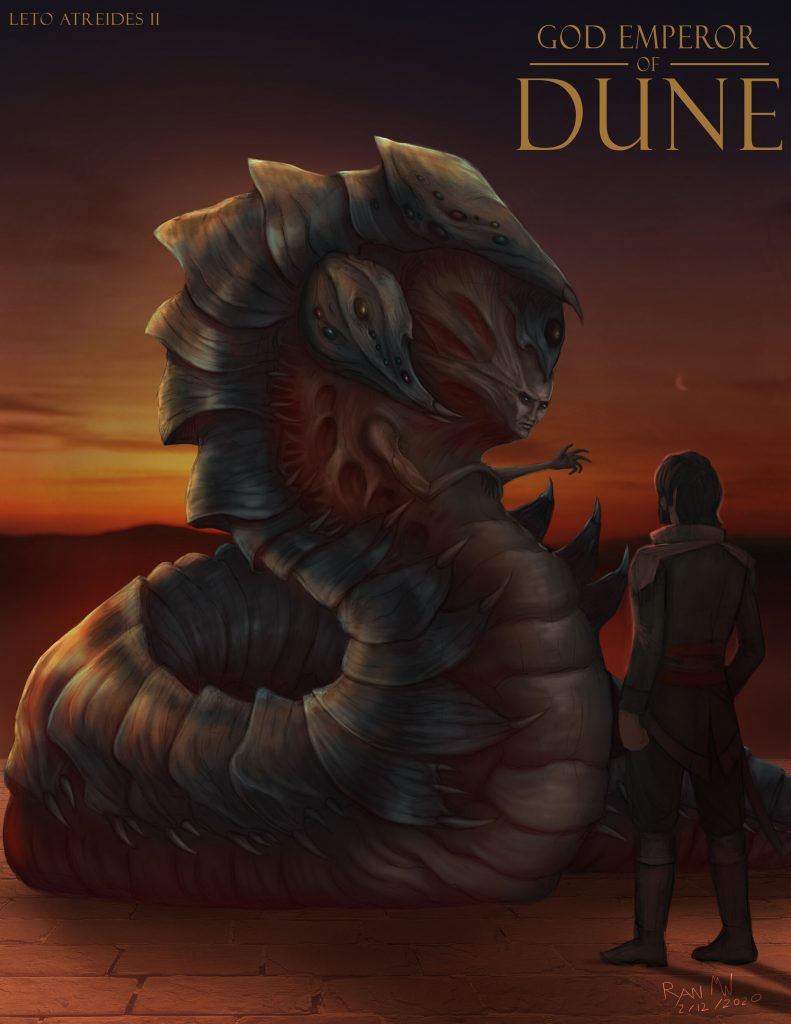

It’s hard to say much about God Emperor of Dune (1981) without risk of spoilers. By the time you get here, I’ll only promise that all of your preconceptions will be blown. The characters you enjoyed in the beginning (if they’re still alive) have been changed dramatically by their respective journeys, and even Arrakis itself is hardly recognizable. Thousands of years will have passed by the end. Some criticize GEOD for its heady politics and theological treatise, but to me it felt like a near-perfect culmination, a shockingly imaginative vision in its own right. There is no lack of story in God Emperor. This book is the distillation of Herbert’s theory of power, sacrificing none of the heroic tragedy that made the first 3 great, taking the whole thing to a new height of epic space opera, educating and tempting like the ramblings of a timeless god.

The desert beneath the storm had taken on a tawny, restless appearance as though dune waves beat on a tempest shore the way Paul had once described a sea. She hesitated, caught by a feeling of the desert’s transience. Measured against eternity, this was no more than a caldron. Dune surf thundered against cliffs.

Chani observes the desert

Now we’re going to get into more detail and review the saga properly. If you haven’t already, just go start reading the thing. We’ll still be here when you’re done.

About the Film Adaptations

(Note: Dennis Villeneuve’s Dune part 1 (2021) is far and away the best Dune on screen to date. A classic movie, epic big budget sci-fi, mostly true to the books and soul of the story, it comes highly recommended for all audiences. As of today it won’t even spoil the deeper series of books! So watch it without fear, even if you haven’t yet read a thing, it’s only going to whet your appetite like crazy. With that said, the rest of this article was written before it’s release however, and I’ve chosen to keep it intact. I’ll follow through with a full review someday, but probably not until Villeneuve’s trilogy is complete. See you in a few years!)

Between Lynch, Jodorowski and the Syfy channel, nobody has yet done Dune any justice on screen. The best adaptation so far is that little series by George Lucas, but it too is a pale imitation. Thankfully Star Wars is as unfaithful and ridiculous as it is derivative, so I’ll tell you that even after seeing all 9, you won’t have any real spoilers for Dune’s long play. But if you’re unconvinced that the 2nd-best-selling movie franchise of all time actually began as a shameless ripoff of this much better saga, let’s just talk again after you review some of the similarities in depth (spoilers). Here and Here are good places to start. Those aren’t just common influences or tropes of the hero’s journey, they are directly appropriated names and specific concepts, in the 2nd-best-selling film universe of all time – enough to make one question the very premise of having IP law at all.

But what Star Wars lacks (despite its sometimes enjoyable, imaginative if incoherent yarn) at each turn is exactly the kind of precision, science, character and just plain writing that Dune provides in spades.

Sadly that soul is every bit missing from the official adaptations of Herbert’s work. You’ll find some fans of the 1984 Lynch movie (David Lynch not among them), and my readers will know I don’t love spending time tearing things down, so we’ll be brief. Love it if you love it, I won’t think less of you. But the cartoonish representation here is just plain weird, nonsensical, hairy, distracting and contrary to nearly everything Dune is in atmosphere, casting and costume. I have nothing but pity for anyone who accidentally saw it before reading the books, and the unfortunate struggle they must have to shake those corny impressions out of their own imagination. The Syfy miniseries are worth a look if you’ve already read through Children and are just feeling kind of desperate to watch the basic plot played out on a screen. Somewhat faithful and sometimes fun, they’re harder to hate than Lynch (go watch Mulholland Drive, that’s Lynch to love), but honestly the Syfy take amounts to little more than a long catalogue of spoilers. It gets better as it runs, so if you’re going, definitely watch it all the way through, but even a young McAvoy can’t save it from being a low budget shadow played out in front of painted 2D backdrops – while still the best adaptation to date.

Jodorowski is fun to watch, after reading at least through book 1, in the documentary about his almost-greenlit 1970s film rendition. There’s no doubt it could’ve been great to watch Salvador Dali play the Emperor of the Universe, in sets designed by HR Giger, with a Pink Floyd soundtrack . . . but would it ever have been Dune? Maybe at heart. At least it was passionate, I won’t knock him there. None of the others can claim anything close to that level of heart.

Hopefully Villeneuve can give us something better in his Dune (2021). I’ve seen the trailers and read the early reviews at this point, and have to say that the casting looks far better than any previous effort. Hopefully they’ll be true to the finer points. I’m a bit concerned that they dropped the word “jihad” entirely, but at least the stillsuits look cool. Herbert’s adherence to Muslim religious etymology regarding the wars of Muad’dib is not some small detail to be swapped out for a Christian counterpart because of weird Western sensitivities. Am I the only one concerned that we cast two pro wrestlers? Did you know Paul, in the books, is not necessarily a white guy at all? I’ll hold my judgment for October though, because honestly it does still look sweet, I’m a little bit in love with Zendaya, and Villeneuve clearly has talent. He wants to make Messiah next! Not Children, Messiah. Be true to the source, interpret it with soul yourself, and some amazing things could happen. The most controversial and supposedly hard-to-adapt plot points are the ones that set Herbert apart as an exceptional storyteller.

Stone burners don’t simply make a person go blind . . .

The Dune Saga: Books I-IV

Reviewed

*Spoiler Warning*

*The rest of this article contains a ton of Spoilers and is really long*

Dune – Review

There is probably no more terrible instant of enlightenment than the one in which you discover your father is a man – with human flesh.

Princess Irulan

I could only imagine coming across a copy of Dune in a bookstore in 1965. Lyndon Johnson was president, US combat troops were fresh in Vietnam, NASA had just launched the first 2-person crew into orbit, and $400 could get you a fancy color TV to watch original episodes of Lost in Space. To a student of Foundation, and sci-fi that ran deeper than the popular golden age fantasies, Dune might have seemed like the next evolution, part of a long progression. There’s no denying its influences (though to my knowledge no incestuous Princess Ollie, giant moles or mystical voice control, swordfights and daddy issues are to be found in Asimov’s Foundation, sorry George). Taking great work for granted is a special kind of treat, and we rarely know when we have it. Serials turned novels and space opera itself were pretty well established, so even the most prescient fans probably just felt like it was a cool new episode in the bigger saga of sci-fi worlds.

What sets Dune apart like a sun among stars, clear enough with today’s perspective, is a seriousness, a borderline hard sci-fi, adult and ecological perspective, and its genuinely interesting, deep cast of characters. It is, in two words, the follow through.

Desert hawks, carrion-eaters in this land as were most wild creatures, began to circle over him. Kynes saw a shadow pass near his hand, forced his head farther around to look upward. The birds were a blurred patch on silver-blue sky – distant flecks of soot floating above him.

Dune

Liet Kynes, from his introduction as a rumor and legend, to his epitaph – wandering the dunes of Arrakis hallucinating about his father and ecological evolution – eventually to his legacy as Leto II’s grandfather, is one of the most underrated of Dune’s many characters. That epitaph is one of the best chapters in the whole saga. Despite all the hype around Muad’dib, Kynes may be the real heart of Dune. I have no qualms with Dennis making his character a female in the new movie. Chani needs a mother just as well. What concerns me is that they make her a real ecologist.

Among its less prophetic elements, in long view, is the patriarchal nature of Dune’s authority structures, but put yourself in 1965 for a second, in the repressed mid-century USA no less, and you might see how characters like Lady Jessica and the Bene Gesserit were revolutionary. There are plenty of reasons to take the contrarian view, no doubt, but understanding Herbert in his time, he was a feminist visionary of early sci-fi. His powerful female leads, while not lacking in beauty or breeding value, are strong in character, judged for their formidable skills, and every bit as instrumental as any male in directing the fate of the universe. Their clothes are often ignored completely (probably part of how Lynch went so wildly off the rails). I couldn’t tell you if they wear makeup at all (let’s hope not), and after reading four books I have no idea what size Jessica’s chest is, though she is prominent on nearly every page of book 1. I’m not going to pretend I’m not curious . . . she’s one of the most interesting characters.

The prudishness of Dune could also be considered an artifact of its time. (GEOD spoiler) The single sex scene in the entirety of the first 4 books is legitimately between a mercenary and a rock. Liberal usage of the word “orgy” notwithstanding, there is hardly more than a kiss or two, and a hug or two in all those 2K or so pages. The love story matters mostly for its genealogical implications.

I had a bit of a thing for Chani long before the latest casting call. It’s hard not to be in awe of her survival skills, loyalty, familiarity with a crysknife, and her general wisdom through the years encompassed by the first 2 books. The fact that I can’t describe anything at all about her grooming is both commendable and boring. Sometimes, especially in the first book, things can be especially dry, and a little physical romance, or anatomical description of either sex might be sorely appreciated, without limiting character a bit, at least for a reader like me. Don’t tell me there wasn’t room.

It is not that power corrupts but that it is magnetic to the corruptible. Such people have a tendency to become drunk on violence, a condition to which they are quickly addicted.

The Bene Gesserit

Dune has headier things on its agenda, and make no mistake Herbert had more than one purpose from the start. The internet will tell you it’s all about the “danger of charismatic leaders,” or “debunking colonial white saviors” but I’m going to call BS on both. Not that he doesn’t have something to say on the matter long before Leto’s grand dive. Herbert even enforced these notions in interviews himself, no doubt simplifying for the masses, but on a more thorough analysis the dual thematic foci of this first novel are absolutely ecology and religion.

Let’s get something sticky out of the way here. Paul’s race, and that of his family, is not clearly defined anywhere in the thousand or so pages of the first 4 books. Taking place 10,000 years in the future, where whole worlds of mankind have evolved into fish-like creatures or shape-shifters, in all likelihood every notion of race as we know it today is a thing of the distant past. Atreides’ roots in Greek royalty do no more to define their whiteness than those of the descendants of Thomas Jefferson today. If you see Dune as a story of a white savior, well that’s just you projecting your views, or your inability to look past Hollywood’s even-today-whitewashing habits. If you see it as a warning about colonialism, you may have missed the part where the Fremen conquer the universe and worship Paul for thousands of years. Herbert, as the OCD mentat he was, had plenty of opportunity to clarify Paul’s race, and never did. Not once. Period.

The Fremen are described as darker, sometimes, but if that is anything other than the ecologist Herbert noting one of many effects of living for generations as nomads in the desert, he gives no hint. The roots of Islam and Christianity are so bound up and twisted together into an altogether rewritten OC Bible, a system of universal religions, as to render all straight-forward cultural comparisons with the world today out of their depth, short of a basic observation of the long-view unity of our different branches in Frank’s world.

Now, as to the purposes of the novel. Herbert claimed it was about charismatic leaders once or twice, you don’t say? Well, I’ve got a thousand of his own pages to tell you it runs far deeper, and darker.

The energy sphere of the planet is there to see and understand. There is a gap in it? Then something occupies that gap. Science is made up of so many things that appear obvious after they are explained. I knew the little maker was there, deep in the sand, long before I ever saw it.

Pardot Kynes

Why is Dune a desert planet? It’s going to seem natural to anyone raised on Star Wars’ Arrakis-like Tattooine, but it was hardly chance for Frank, or typical of his time. He built around the idea with layer after layer of conversation about the inevitable transformations of planetary biospheres. Sure, Star Wars and Dune are both examples of a classic hero’s journey, borrowing much together from Greek myth. But where one launched straight away into space cowboys, “lasers” and fascists in penis helmets, the other used the realistic version of this desert setup as thin cover for a discussion of environmental science, hardship and survival, 3 years after the publication of Silent Spring. Ahead of his time, Herbert was a student of the sand well before he wrote the book, and saw the fluid nature of ecosystems with more clarity than many of his contemporaries. Dune, book 1, regarding ecology alone, could be considered hard sci-fi. Of the major themes present in the first four books, planetary ecological warning is one of the two most central. Water. Is. Scarce. Survival. Is. Hard. We have it really nice on Earth, if we don’t fuck it up.

Overflowing with other concepts, some scientific but many fantastic, Dune is not to be pinned so easily. Primary among the rest, winding around the ecological narrative like two strands of DNA, is the nature of real prophecy. Contrasted with the machinations of religious organization, and how that all relates to power, Herbert is doing nothing so pedantic as just warning you about following stylish leaders, no matter how tempting that simplification was, even to him.

By the end of Dune, Paul has definitely found his inner charisma, wholly succumbed to the mystique of his own prophecy, and toppled the emperor of the universe, but there is no danger in this, at least not for the Fremen or any of the good guys. We’ll cover Messiah in a minute, but even in the long view only a minority among the survivors will ever consider Muad’dib a bad guy.

In truth one of the bigger flaws with book 1 is its more easily apparent roster of good and bad guys. I can almost see how Lynch thought the Baron ought to be a cannibal in a cape. As the only representation of anything non-hetero anywhere in book 1, Vlad’s love for men and boys is a little cringe-worthy, and not the only dated part of things. I’ll only suggest that for a patient reader, Herbert does, eventually, vindicate himself on this, as he does on other biased gender roles and any questions of eugenics.

As far as themes of colonial heroics, an attentive reader may well see that the Fremen (can’t we just agree to pronounce “Freemen” like I did while reading?) are actually the ones that liberate and educate Paul, go on to conquer the universe, and transform their planet. Good writing, like history, is not and should never be a process of appeasing the masses, or even owing some sort of debt to morally simplify. Herbert does not say that gay people are evil, and he does not say that colonizers are good. If anything, in the larger cast populating the universe of Dune, both the Baron and Paul are outliers.

Though it does stretch the suspension of disbelief at points. We’re talking about a future so far removed that some branches of the human tree have basically evolved into fish, and yet nobody has come up with a better system by which we can all relate, than the tired old tragedy of class stratification, with its incessant mistrust, ego and violence? I guess, without royal intrigue and economics most of the Dune saga would fall apart, and so lose the critical balance of entertainment it so expertly maintains. If spice could be synthesized – as realistically all elements can, given the immensity of space and the progress of science – Leto II himself would have no claim to power. But I’ll be honest, to this reader nobles aren’t inherently very interesting, assassination plots and betrayals notwithstanding, and even less so the movements of little pieces of paper by which various egos consider themselves to have acquired “wealth” and “influence.”

No less silly is the constant stream of near-death encounters between characters in the world of Dune. If I had a ‘thopter for every time a crysknife was almost drawn because somebody’s feelings were hurt, or a spiceblow for every time someone demanded a duel over honor, I’d be the richest man on Arrakis. Maybe I’m a minority in believing we’ll all be far past scarce resources, worshipping royalty and fighting over every inconvenience by the year 10K – but I’m holding to it nonetheless.

Does the prophet see the future or does he see a line of weakness, a fault or cleavage that he may shatter with words or decisions as a diamond-cutter shatters his gem with a blow of a knife?

Princess Irulan

So the way Dune kept me in, despite these common distractions, is a testament to the depth and versatility of Herbert’s talent as a storyteller. Most games of thrones are just pretty boring. What we have here isn’t so simple as a story of a monarch and his tireless wars.

What is prophecy, and why is it so important in Dune? Herbert counterweighs his ecological treatise with this question, forging no lightweight theory. Without hitting us over the head, he manages to rewrite the Bible, building a theory of religion that bridges eastern, western and Muslim traditions from today, without apology both appropriating and dropping various maxims and traditions. This amalgamation is strangely ignored by most Dune critics, who love to point out the Arabic influences in the language while minimizing those from western culture and even Zen Buddhism. Herbert has bigger fish to fry (excuse the pun) than our petty modern idol worship. The Dune saga incorporates Christianity without Noah, Agamemnon without Hades, and Jihad without Shariah. Bolder than the average philosopher, he cuts to the chase, describing a manipulative, self-fulfilling religious conspiracy of millennia, yet never quite vilifying its power even so. Kwisatz Haderach is derived from a Hebrew concept of saints, meaning “one who can be in two places at once,” just as Herbert used it. The line of religious lineage becomes clear, in rare form, by contrast with prescience – the psychic act of knowing the future.

Dune describes a theory of time informed by Einstein, a topology like any landscape, with hills and valleys, where often the comparison is made directly with the desert itself. It is more than casual symbolism, amounting to a serious sci-fi system of foresight. The entire work can be seen in fractal form – where the innermost whorls reflect outward at larger and larger scale – from the dreams of young Paul to the adventures of the descendants of Muad’dib – from eddies in the sand to great coriolis storms. Time is like a desert, says Dune, landscapes of sand are like time, and we are but small travelers. Foresight is no miracle but a sense like any other, as we witness the very real landscape of our potential futures.

There’s more to discuss, from drugs to language to technology, worms, rituals and weaponry. For now let’s move forward and look at how things evolve in the sequel.

Dune Messiah – Review

What is the son but an extension of the father?

Princess Irulan

If we we’re lucky then, after taking Dune completely for granted in the 60s we might have picked through Flowers for Algernon, Logan’s Run and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep in the following three years, and thought it really was a continuing golden age. Most likely we wouldn’t have known a sequel was in the works, until Dune Messiah dropped on bookstore shelves in 1969. A lot of things were going on, anyway, you might try Googling it. The same year, men landed on the moon.

There would be no Star Wars at all for eight years yet, and hardly the pox of sequels we have today. Dune 2 is not popcorn fodder, and is not written for kids but for all ages. If Dune is a greek hero’s journey, then Messiah is more Shakespearean – tragic, reveling in character flaws and moral ambiguity. For those with the eyes to see, Messiah was an upping of the stakes, taking things in unexpected, dark and controversial directions. This wasn’t a new corporate writer taking unwelcome freedoms with established canon (ahem), but an original creator boldly doing with his creation as he saw fit.

Herbert pulls the rug out from under us at the start. Twelve years have passed, the Jihad of Muad’dib has conquered the universe, killing 61 billion souls, wiping entire cultures and religions from existence. We are introduced to new characters and races in the first pages, revealing technology and evolutionary branches that, if the arc had been planned from the start, probably should’ve been talked about before this point.

Throughout Dune, we’re given foreshadowing of a holy jihad and terrible purpose, and these events must logically follow the awesome climax of book 1. Yet when we arrive in Dune Messiah, they are apparently already past. Our hero is suddenly a questionable ruler, comparing himself even to Hitler. The inner court has already turned against him, including no less than the Princess Irulan in their conspiracy. Even the rules of the universe itself seem to have changed to allow for shape-shifters, fish-men and clones with metal eyes.

The cast of characters is smaller, the set pieces fewer and more intentional, and overall Messiah has the feel almost of a play rather than an epic novel. That is if plays could properly model atomic weapons and eyeless gods. A reader looking for further meddling from the notorious Count Fenring, or eager to learn much about Lady Jessica, will be sadly disappointed. It is notably the shortest book of the saga.

So the triumph of Dune Messiah is really an achievement. It takes the series in a new direction, showing Herbert to be a master of multiple formats – science fiction, drama, philosophical dialogue – and most importantly a wizard of the unexpected, of the wildest depths of imagination.

The new factions are anything but thrown together. The Tleilaxu and Ix make perfect sense in the universe built up so far, fleshing it out in new ways. Maybe if great minds like Herbert weren’t forced to justify themselves in serial publication, the whole would hang together perfectly. But in the world we inhabit, the only way a saga like Dune can be made is piece by piece. These minor breaks in consistency remind us that all we’re doing is enjoying a story, told by an actual human being. In any case, as strange as face dancers and navigators may be in the flesh, it eventually becomes clear that they are mankind yet, evolved in the far reaches of space, over thousands of years.

By the end we’ll see stone burner atomic weapons, manchurian assassins and a teenage Princess Alia, heir to her ancestors’ memories, better trained than anything the world can throw her way, aggressive and loyal to her brother even when no one else seems to be. Paul loses his eyes – ghastly holes where the organs used to be – becoming a ghost-like god himself, still able to see better than anyone else, frightening in the certainty of his terrible decisions. All of this amounts to something much less expected, and so more rewarding, than just another space war.

But I have answered you! Have I not said the myth is real? Am I the wind that carries death in its belly? No! I am words! Such words as the lightning which strikes from the sand in a dark sky. I have said: “Blow out the lamp! Day is here!” And you keep saying: “Give me a lamp so I can find the day.”

Muad’dib

Nothing will speak better for Messiah than the Desert Mouse himself.

There are many degrees of sight and many degrees of blindness. His mind turned to a paraphrase of the passage from the Orange Catholic Bible: What senses do we lack that we cannot see another world all around us?

Muad’dib

Chani’s character arc fulfills tragically, the ghola Hayt (Arabic for life, English for hate) redeems himself and regains his soul, Alia rises and falls in love, and Paul transcends his own myth, giving up everything to wander defenseless into the desert. Consistent throughout on its own terms, the same prescient shielding that kept Edric’s conspiracy from him, shielded the birth of Leto II. Breaking free of his visions – by choosing to give himself to the mercy of the ghola of Duncan Idaho and refusing the gift of Chani’s resurrection – leaves Paul truly blind, in a future he never foresaw. Yet preborn Leto II, sharing his eyesight miraculously with his father, saves himself from the shape changing assassin. If you’re bored at the end, you certainly weren’t paying attention, but Herbert doesn’t hold our hand through all of this, so hopefully that little run through helps clarify it all for some.

“Nothing hides in such a night! What rare light is this darkness? You cannot fix your gaze upon it! Senses cannot record it. No words describe it.” Her voice lowered. “The abyss remains. It is pregnant with all the things yet to be. Ahhhhh, what gentle violence!”

St Alia of the Knife

In Dune Messiah, Herbert explores the dark side of power from within. No Harkonnen ever dared the crimes of the tyrant Muad’dib, but Paul is as thoughtful a leader as ever there was. We can choose to trust him or hate him, but he has foreseen that the 61 billion deaths under his reign represent a path far better than its alternatives. Tortured even still by the inevitability of his terrible purpose, we are likely to wonder by the end if worse things are actually in store for the future of Dune than jihad.

Children of Dune – Review

“To be sighted in the land of the blind carries its own perils. If you try to interpret what you see for the blind, you tend to forget that the blind possess an inherent movement conditioned by their blindness. They are like a monstrous machine moving along its own path. They have their own momentum, their own fixations. I fear the blind, Stil. I fear them. They can so easily crush anything in their path.”

Leto II, age 9

“I can think of nothing more poisonous than to rot in the stink of your own reflections.”

The Lady Jessica

Seven years have passed in the real world, and nine in the world of Dune. The Viking 2 entered orbit around Mars. Microsoft and Apple are both brand new companies. Ringworld, The Lathe of Heaven, The Stepford Wives and Flow My Tears the Policeman Said may have kept us entertained with a flow of great new sci-fi, but nothing near the epic worldbuilding in Children of Dune came to mainstream bookstores, possibly ever, prior to 1976.

Alia has grown up. Taking the reigns as Regent of the universal empire of Muad’dib, she has codified his religion and rules less with an iron fist than a wormstooth knife. Alia, like her brother before her, became a casual murderer as fast as a ruler, and like her brother this happened between books. For the second time we have the rug ripped out from under us at the start, having to accept that a character we loved has already fallen from grace, out of sight. Minor foretellings aside, a faithful reader could be forgiven for feeling betrayed by our preborn-warrior-Princess-turned-callous-Queen-of-Hearts.

After Chani’s death Paul disappeared, and now a mysterious blind Preacher has emerged, nameless and guided by a boy, shouting inconvenient truths at the religious mobs that emerged in the wake of Muad’dib. They worship his legacy, but forget his message, or so claims this Preacher. Paul’s children – Liet’s grandchildren – the twins Ghanima and Leto II, are 9 years old, wise with the preborn experiences of thousands of ancestral lives. A plot is in the works against them, including nothing less than remote controlled, genetically augmented murder-tigers.

Herbert is in rare form, and it’s not strange that Children is often a top contender for the best of his work. Weaving together the mammoth world-building of Dune, the Shakespearean tragedy and Socratic dialogue of Messiah, with an altogether fresh exploration of childhood, maturity and the temptations of power, he comes armed to the teeth with raw scope. The kind of thing that simply couldn’t exist without a prior decade of work, CoD is the point at which Dune redefines space opera. More character-driven epic than adventure, Children of Dune remains to this day a powerhouse of what is possible in thoughtful, slow-build sci-fi. In one word you might say, like the spires of a cathedral-castle at the center of the universe: culmination.

“I articulate the myth and the dream! I am the physician who delivers the child and announces that the child is born. Yet I come to you at a time of death. Does that not disturb you? It should shake your souls!”

The Preacher

Entire pages of CoD are quotable, as Frank finds his stride and arrows of truth just ribbon out of his mouth like some kind of enlightened borealis.

“I mean to disturb you! It is my intention! I come here to combat the fraud and illusion of your conventional, institutionalized religion. As with all such religions, your institution moves toward cowardice, it moves toward mediocrity, inertia, and self-satisfaction.”

The Preacher

For those who have seen the Litany Against Fear trotted out, time and time again, as the quote gratis of the saga, I can’t help but just copy out a few slightly more brilliant and underseen lines here. Can I get an amen? I’ll settle for memeification.

“You, Priest in your mufti, you are chaplain to the self-satisfied. I come not to challenge Muad’dib but to challenge you! Is your religion real when it costs you nothing and carries no risk? Is your religion real when you fatten upon it? Is your religion real when you commit atrocities in its name? Whence comes your downward degeneration from the original revelation? Answer me, Priest!”

The Preacher

“Leb Kamai,” she whispered. “Heart of my enemy, you shall not be my heart.”

Ghanima Atreides, age 9

Children of Dune is essentially a story of two concurrent character arcs: Alia’s temptation and fall from grace, and Leto II’s introspection and rise. The Preacher, Duncan Idaho, House Corrino and Lady Jessica have much to say about it all, but it is Alia and Leto II that drive the plot of book 3, from the opening to the final lines. The reader may begin to wonder which character is actually the Kwisatz Haderach after all, and which, if not all of them, is the feared abomination.

When the toddler Princess Alia killed the Baron Harkonnen in book 1, it was one of very few points in the too-serious reading where I actually laughed – it was just that rewarding, her raw intellect and confidence overcoming the arrogant Baron so unexpectedly. In book 2, her breaking the record against the training robot, at 15 and in the nude no less, was easily one of the most charged moments in the entirety of the otherwise sexually-inert saga, pushing the reader’s sensitivities both to her age and to the incestuous tension apparent with her brother, himself the young tyrant-Messiah. Are we seriously less offended by a murderous toddler than a naked, smart and self-empowered teenage girl who can clearly defend herself? Asking for a friend.

So witnessing her descent through book 3 was difficult for me from the start, but by this point I was prepared for Frank to upend my expectations, ready to ride whatever unpredictable plot he may’ve sprung.

Execution in Alia of the Knife’s court is acceptable before we arrive, without any need of abomination. Maybe that’s just the nature of Arrakis, where honor-killings are as nondescript among the respected natives as mice in the desert. Throughout the first 3 books the Fremen respect for life is tenuous at best. In a hard desert, life is hard, I get it. Water is scarce – sometimes you may have to drink your friends. So whatever Herbert’s thoughts about charismatic leaders, it’s clear in the world he created for this saga that murder is hardly an original sin, whether you are king, prophet, princess or a slighted peasant.

So what does Alia lose, when she cracks under the pressure of the ancient personas fighting in her psyche and allows the spirit of the dead Baron to usurp her future? It isn’t the sanctity of life. It’s not her compassion, loyalty or vision, all of which died somewhere between the publication dates of books 2 and 3. If the Baron subsumes her will, driving a wedge deep into her divided mind, it is only possible because she had, years prior, given herself to the lies of vanity. As Herbert insightfully points out, violence is addictive. Increasingly desperate to cling to the ledge of her brother’s abdicated, god-size pedestal, unable to ever gather herself under the protective skirts of his truth, throughout Children of Dune we witness her steady disintegration, smothering under a mere ghost of a memory of the Baron. He was gross, conniving, but had what she lacked: fearless and united in a single purpose. Alia is born into royalty, already wise, and grows up beautiful, well trained like no other. Plummeting from the window of her own tower, she dies yet a victim of power she hadn’t the vision to hold.

It’s a tragedy like few others in the halls of science fiction. Maybe it’s not quite Macbeth, but it’s closer than most.

“One uses power by grasping it lightly. To grasp too strongly is to be taken over by power, and thus to become its victim.”

Duncan Idaho

Leto Atreides II at 9 years old isn’t your average child. Preborn, awake in the womb with all of the memories of his collected ancestors, he is wise with the power of a full-grown, well studied Reverend Mother of the Bene Gesserit before anyone is ready to deal with him. More reserved than Alia – in fact prescient to her warnings before even she understands them – he is not without hesitation, not without doubt and deliberation throughout Children of Dune. But if Alia goes out in a flash like a flame, burnt by the raw, kinetic energy of her own rule, then Leto II is her phoenix, reborn, young and alight with every bit of vision she could never find.

McAvoy may be the best thing about Syfy’s Children miniseries, but you can’t deny he’s more than twice the character’s actual age. At 9 years old, nobody takes Leto II seriously, even as he runs circles around their logic, evades their best laid traps, slaughters mutant tigers and enters a spice-trance inaccessible to anyone other than his father, the emperor of the universe, Muad’dib. He is thoughtful, intelligent and more capable than natives who have spent their lives perfecting survival in the desert. As the book goes on, and he becomes more and more aware of his true abilities, he gets bolder. Entertaining the psychic ghosts of a thousand generations of rulers, dating back to prehistory on Earth, he faces down the lessons of history with all of the honesty of a born leader. When he finally enters the sandtrout stream, merging his flesh with the pre-worm supercreatures of Arrakis (the only true alien lifeform we have likely seen to this point in all of the saga), he takes on physical abilities to match his mental leaps, and nothing can stop him.

Leto II, age 9, covered in sandtrout skin – rubbery and shining in the desert light of two moons – leaping from dune to dune, becomes a living metaphor. If time is like a desert, Leto II is like our 6th sense set free, a young traveler at home, everywhere at once, traversing hills and valleys like a bird riding currents of the sky.

Nothing about this is accidental. Herbert has a catalog points to make. By and large he is very direct with them. If you won’t accept the teacher, you will not learn the lesson. Leto II should not be played by a 20-year-old actor any more than Muad’dib should lead a war of Catholic conquest.

I’d love to make room to discuss the underutilized Ghanima, the changes in Jessica, Idaho’s second sudden death and even the redemption arc of young Farad’n, but for the sake of brevity I’ll refrain, with the suggestion that we all go back and read it again sometime. At least we know Leto II is on the right path.

God Emperor of Dune – Review

Leto looked toward the setting sun. It floated low to the horizon, faded a dim orange by a recent storm. Rain crouched low in the clouds to the south beyond the Sareer now. In a prolonged silence, Leto had watched the rain there for a time which had stretched out with no beginning or end. The clouds had grown out of a hard gray sky, rain walking in visible lines.

3500 years have passed on Arrakis by 1981, with only five on Earth. One can only assume this is confirmation of Einstein’s time dilation, and that works of fiction may at times break the barrier of light speed. In fact, if ever they have, God Emperor of Dune is that book.

A Scanner Darkly and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy may have kept us busy in the interim, but nothing was to prepare the average sci-fi fan for the omnibus of imagination that is GEOD. At a time when Bermuda shorts were considered forward, Leto II crashed into the genre, nothing less than a giant, narcissistic man-worm on an out of control dais.

From the opening chase, with its dire wolves out of space, God Emperor is Frank Herbert without the brakes. Unrestrained – love it or hate it – this is the polarizing book that he wrote simply because he wanted to – exactly how he wanted to. Philosophically grandiose, creatively perverse, uncompromisingly heady yet more action-packed than anything since book 1, Leto II’s life story is an epic for the ages, a fitting capstone to the first half of the Dune saga and a bridge to the rest.

Like the rest of Dune, GEOD isn’t without its flaws, but if you’re a fan of science fiction and you haven’t yet read it, well get off your ass and give it a go. While we’re likely to get a full trilogy and maybe even more from Dennis Villeneuve’s new movie franchise, it could be 3500 years before we see a fitting cinematic adaptation of the God Emperor. This is a book for book lovers, sci-fi for the fearless, unadaptable by common standards. Dig in.

I know the evil of my ancestors because I am those people. The balance is delicate in the extreme. I know that few of you who read my words have ever thought about your ancestors this way. It has not occurred to you that your ancestors were survivors and that the survival itself sometimes involved savage decisions, a kind of wanton brutality which civilized humankind works very hard to suppress. What price will you pay for that suppression? Will you accept your own extinction?

Leto II

Paul’s second son puts at last an end to any debate about the Bene Gesserit’s foretold Abomination. 80% sandworm, 10% man and 10% actual god, Leto II is the bestial monstrosity gone galactic. The Jihad of Muad’dib may have killed 61 billion over 12 years, but by the time we find Leto II in his crypt it has been over 3500 years, and the unspoken toll is beyond mere numbers. Having reduced his universal empire mostly to base agrarian lives, the force implied – like the God Emperor’s lack of empathy – is gargantuan. Thousands of years of history has simply vanished in his shadow.

Is he God? No, clearly, but as a hybrid Shai-Hulud that knows both future and past like a vulture knows the desert, he is about as Godlike as a man can be. Unable to create life, he yet orders it done, and the Tleilaxu clone for him Duncan Idaho after Duncan Idaho, each with memories only of their first life on Dune. Leto breeds him with chosen Atreides stock, building not to a simple Kwisatz Haderach, but to a potential race of them, in his long-descended heiress, Siona.

Despite his inhumanly rational mind, Leto II the Worm-god suffers the kind of emotional Tourette’s you might expect of a human two-year-old set loose in a room of delicately hand-painted model trains – less God, more Godzilla. His close aides are never sure when he might lash out and send them flying into a bloody heap. With wisdom so serpentine, they are never quite safe from offense that could set off the beast.

Yet the Tyrant Leto II is not easy to hate. Maybe I’ve been desensitized by decades of progressively violent media, maybe I’ve learned how to suspend my disbelief a little too well, but even though this guy remorselessly slaughters his best friend over and over again for centuries, even while he rationalizes oppression without ever quite telling us why, I can’t help but see his face, in that worm-fat cowl, as human. What would it mean to remember all of our previous genetic lives? How much smaller might our little deaths appear in the span of thousands of years, across so many passions, losses, fears and hopes? What would it be like to remember the future, and know that even though you have a choice, the best way is far from the easiest – and not just for you – but yet as clear among its options as a Golden Path in a mire? Maybe, while Frank was selling the world his tale of charismatic leaders, he was actually, slyly, teaching us compassion for tyrants.

“I have no allies. Only servants, students and enemies.”

Leto II

Even as a long-form reader of the saga, by the time I met Hwi Noree I was not prepared for the way Herbert sneaks major new characters in under the radar. Even after Children of Dune I wasn’t prepared for anything like the God-worm fate of young Leto II. If you were able to make it to GEOD without anyone spoiling the major plot points of the saga, like I was, count yourself among the lucky few. Hardly anyone in popular culture doesn’t know that Vader was Luke’s father, so the experience of shock at such a twist in the plot is very rare today, and eventually that is likely to become the case every bit as much with Leto II the Worm Tyrant son of Muad’dib. Except of course that Leto II would see Vader coming before either of them had taken a single breath of air.

“You have faith in life. I know that the courage of love can reside only in this faith.”

Hwi Noree

Reductionists have called Frank Herbert’s philosophy nothing more than Libertarian preaching, but I’ll tell you they’re missing the finer points by a mile. While he has much to say criticizing government, there’s a lot more going on here than ending taxes.

Imagine the love required of the sacrificial son who doesn’t merely die for his people, but instead lives for thousands of years as an abomination, a tyrant and murderer, friendless in a boring infinity, hemmed in on all sides by the vision to see that all paths are lesser than one, imprisoned by a golden truth that shines, impolitely bright, on every unwelcome but necessary tragedy of a future governed by yin and yang. Achieving balance, peace and security for the race means giving up his own humanity, but not being allowed an end to his life. Well, eventually it means that too. Yet compared to living thousands of years in an unlovable prison of oddity, incompatibility and idolization, making the hardest of hard decisions with the certainty of a crysknife, death, to Leto II, is clearly not a thing to be feared.

“You seldom need words. You speak directly to the senses with your own life.”

Hwi Noree

If that were true, God Emperor of Dune would be a short book indeed. Still awesome, but maybe around 100 pages. In those 100 pages we get forest-dwelling dire wolves, all-girl/worm orgies with God (where everyone just kind of stands around chanting), an original backup cast – including Nayla the devout Fish Speaker spy, Moneo the uncertain but faithful scribe, numerous Reverend Mothers and two brand new Duncan Idahos, the rebel Atreides Siona, deserts, villages, cathedrals, and a crypt where the universal ruler takes his throne. Hwi Noree comes in somewhere nondescript in the middle. It’s Dune, so there’s plots, feuds and endless attempts at assassination, but honestly these were some of the less interesting parts at the start, let alone a thousand pages deep. Herbert will be Frank though, and it’s hard to imagine the book existing without them. Siona is the balancing force that finally catches up with Leto II, Idaho surely has more cause to regicide than the old Baron ever did, and Nayla’s whole purpose is somehow about the Judas curse of blind devotion, so this reader will accept the feudal setting’s endurance even 13500 years in the future, if it is what the author has to tell.

The other 300-odd pages of God Emperor is Leto II talking. Which is cool by me.

In all of my universe I have seen no law of nature, unchanging and inexorable. This universe presents only changing relationships which are sometimes seen as laws by short-lived awareness. These fleshly sensoria which we call self are ephemera withering in the blaze of infinity, fleetingly aware of temporary conditions which confine our activities and change as our activities change. If you must label the absolute, use its proper name: Temporary

Leto II

“You are God embodied. You walk around within the greatest miracle of this universe, yet you refuse to touch or see or feel or believe in it.”

Leto II

What is the most immediate danger to my stewardship? I will tell you. It is a true visionary, a person who has stood in the presence of God with the full knowledge of where he stands. Visionary ecstasy releases energies which are like the energies of sex – uncaring for anything except creation.

Leto II

Most civilization is based on cowardice. It’s so easy to civilize by teaching cowardice. You water down the standards which would lead to bravery. You restrain the will. You regulate the appetites. You fence in the horizons. You make a law for every movement. You deny the existence of chaos. You teach even the children to breathe slowly. You tame.

Leto II

“Right where you stand, you are in the unmistakable midst of Infinity. Look around you at the meaning of Infinity.”

Leto II

You’ll hate him for arrogance much quicker than for murder, odds are, but it’s hard to argue with this guy. Stuck in the middle of an empire for millennia, slowly becoming a worm, hated, feared and idolized by all of the races of man, yet alien in his own skin, Leto II is bored, more than anything. He craves surprise, even if it kills him – even if it kills you. Evolved with the presence of thousands of lifetimes of experience, no warlike inhumanity, no odd perversity, nothing at all phases him until he’s confronted with the wonder, honesty and faith of Hwi Noree. Raised in secrecy, in an attempt to lull him into assassination, Hwi is unexpected by God, and so he loves her like he couldn’t love anything else.

Even though, as Herbert is sure to point out more than once, his worm-dick won’t be going anywhere near her. In the sexless intergalactic drama that is the first 4 books of the Dune saga, GEOD stands out as an oddity. Sexless orgies, a worm that’s in love but explicitly has no penis, and Nayla’s spontaneous orgasm – while staring at a rock – make one wonder if it’s not all a little more intentional. No, I think it’s a product of the prudishness of its times, in all honesty, more than anything, though for a major science fiction release in the early 1980’s, maybe even ahead by a bit. Herbert isn’t promoting intra-species bestiality any more than he was advocating for 15-year-olds to risk their lives in the nude against training robots set to 11, or for toddlers to play with the Gom Jabbar. This is just Frank’s imagination run wild over boundaries, set free, reacting to novelty in novel ways, like Leto II on his good days, almost like a child born with the wisdom of all generations – still curious at heart.

“I will tell you this only once. Homosexuals have been among the best warriors in our history, the berserkers of last resort. They were among our best priests and priestesses. Celibacy was no accident in religions. It is also no accident that adolescents make the best soldiers.”

“That’s perversion!”

“Quite right. Military commanders have known about the perverted displacement of sex into pain for thousands upon thousands of centuries.”

“Is that what the Great Lord Leto’s doing?”

“Violence requires that you inflict pain and suffer it. How much more manageable a military force driven to this by its deepest urgings.”

“He’s made a monster out of you too!”

“You suggested that he uses me. I permit this because I know that the price he pays is much greater than what he demands of me.” – Moneo speaks with Duncan Idaho

“You have amused me, but take no heart from that. Lately, I cannot separate the comic from the sad.”

Leto II

“I have seen peoples and planets in such numbers that they lose meaning even in imagination. Ohhh, the landscapes I have passed. The calligraphy of alien roads glimpsed from space and imprinted upon my innermost sight. The eroded sculpture of canyons and cliffs and galaxies has imprinted upon me the certain knowledge that I am a mote.”

Leto II

“I have seen people and their fruitless societies in such repetitive posturings that their nonsense fills me with boredom.”

Leto II

Things move. It is an ultimate pragmatism in the midst of infinity, a demanding consciousness where you come at last into the unbroken awareness that the universe moves of itself, that it changes, that its rules change, that nothing remains permanent or absolute throughout all such movement, that mechanical explanations for anything can work only within precise confinements and, once the walls are broken down, the old explanations shatter and dissolve, blown away by new movements. The things you see in this trance are sobering, often shattering. They demand your utmost effort to remain whole and, even so, you emerge from that state profoundly changed.

Leto II

He is both ship and storm. The sunset exists in itself.

Moneo

Remember what I did! Remember me! I will be innocent again!

Leto II

Like most of the saga, God Emperor of Dune is chock full of characters that know the future, and know how dark and dangerous and terrible it must be, but never quite tell you about it in any certain terms. We hear you, Leto II, the Golden Path is the only way to save humanity from ourselves. Just like Muad’dib, killing those 61B was actually a kindness, we get it, because every other path was worse. And Paul wasn’t strong enough to take the sandtrout skin, to become the abominable Haderach the Gesserits foretold would come in the next generation anyway, as it then did with the Worm-god. After a thousand or so pages I’m well aware that they both chose the only way forward, and it included slaughtering and oppressing the masses like nobody in Earthly history could even imagine. What I haven’t got though, is why. What did Paul actually foresee? What is Leto II steering us away from? By the time I got through book 4 I began to understand that maybe Leto II is what Paul foresaw, but seriously, expecting a reader to be patient through 4 books to get there is pretty bold. Maddening even. And it gives the distinct impression that, as much as the saga does hold together in the end, Herbert was actually making it up as he went along. In fact Paul could have foreseen literally anything, so long as it was terrible. That’s all that we actually know about his revelations, even after 4 books. For some reason he just never gets around to telling us.

Rather than a simple political warning, Herbert seems to be saying something about the impossible difficulty of the real choices inherent in leadership. In a universe of dualist forces – yin and yang, so to speak – life must be balanced by death. Freedom only comes at great cost. Security can only be bought by unfathomable loss. Technology destroys. Peace leads to decay. Leto II turns Arrakis green at last, completing the long arc of Liet Kynes’ original vision, but in lakes, rain and lush grassland mankind is made weaker, not stronger. It is through struggle that great men are made, or so, clearly, goes the philosophy of Dune.

And Herbert definitely spells that out plenty. But is saying it the same as showing it?

Even so, rather than true prescience in itself, the Dune saga is actually concerned with a vision of the nature of time. If years come and go like dunes beneath a traveler’s feet, sometimes rising into view ahead, other times mysterious as valleys beyond horizons, then maybe we are all, in the long view, a little more like Leto II than we may have thought. The sum of your ancestors could be envisioned like the links on the body of Shai-Hulud, the thrust of our genome plowing through time like a worm in sand. And given enough time, broad with enough dunes, we disintegrate – like a worm on Earth is an agent of biological regeneration, the eater of the dead. Are we spice, in the end? Is it the fragmented body of the Worm that turns our eyes toward the sky, after the longest of long evolutionary curves? By studying these grains, these endless corpses that gather our ancestral wisdom, we may even see the future.

Or maybe that was just the drugs.

“All contemporaries do not inhabit the same time. The past is always changing, but few realize it.”

Leto II

I’d love to get deeper into the technology, etymology and art of Dune, but my waning sense of brevity won’t allow more than a few one-offs here. While the time Herbert put into developing this awesomely unique universe is clear, a seminal world-building achievement and no less, there are yet a number of inconsistencies. There are way too many useful techs that never reappear. Hunter-seekers, Gom Jabbars, Stone Burners and more simply show up when needed and then fade into the background of the series, as if nobody ever thought of using them twice. Sure, atomics present a mutual destruction scenario, but are you telling me that nobody in the whole universe of Jihad has imagined their suicidal use? The same is true of the relationship between lasguns and shields. Are we really so sure that the atomic result of their combination is a deterrent? For that matter, why do shields exist in the Dune universe at all? They seem cool, perfect for a good knife duel. Then, over the course of a thousand pages and dozens of knife fights, I don’t think there was a single instance of a useful shield at any time outside of training. Not one. It’s pretty clear that Frank just wrote these parts as he came up with them, and a lot of them never quite fit coherently into the bigger picture.

So it sure would have been interesting to get Frank Herbert in a different universe. One where he didn’t have to justify his vision with serial publication and so many side jobs. How many will remember the author of Dune for his work as a political speech writer? I venture a hopeful zero. Given the time to polish, and the freedom to follow his unique imagination from page one without ever cowing to editors and audiences, I can’t help but feel there’s a chance we would have had even a superior saga. Dune is epic, practically incomparable, deep and engaging, but not without the flaws inherent in being told by a man who even still had to keep it secondary to “real life.” 50-odd years after its first publication it holds up just fine as a pinnacle work of early space opera, but it would be a lie to say it doesn’t show its age at all. If God Emperor is any sign of the direction he would fly, set free by his own success, well I would love to have given him more time. Those 23 editors that couldn’t see his worth be damned. Nobody will remember their names.

“The right is known because it endures.”

Leto II

As an ecological treatise, the saga may in fact be timelier now than ever.

The language of Dune is a monolith of its own, reminiscent of Tolkein if not Shakespeare. For a student of etymology like myself, the breadth of Herbert’s love of language is awesome. You’ll read a lot about how it’s inspired by Arabic roots, but there is so much more going on here that it’s a little mind blowing to anyone with the time to do their research. Even for those more passively inclined, you will want to keep a dictionary at hand while reading. Only a few pages generally went by between each time I pulled up a Google search after coming across a strange new word or phrase, wondering if it was real, or something he just made up. From the Kwisatz Haderach to Hayt, a search will almost always teach you something you didn’t know about language and the roots of Dune itself. If anyone has a good anagram study of the saga, shoot me a link! That goes a bit above my head, honestly, but I’m attuned enough to see that he made use of the idea more than once.

I’ll end with a nod to the remainder. What’s to come in books 5 and 6 may well prove my theories better or worse. I’ve heard he lets loose with more sex, raw adventure, Space Jews and No-Ships. But I don’t want to spoil it, for you any more than for me.

I’ve heard that the Brian Herbert expanded universe is not as good, starting with books 7 and 8 based on Frank’s notes for the end of the original saga before he died. Based just on his Forewords in the Collector’s Editions, I can already see that will hold true. Maybe I’ll find time to read all the stuff that could have happened to Lady Jessica on Caladan some day, but honestly, by the time I get through book 6 (or maybe 8) that may be enough to chew on for a long, long time.

Because Dune isn’t a saga like Star Wars, where the world building is just a shell in which endless adventures can take place so long as people are buying.

Dune is a metaphor, for time. It is a lesson, about power. Duncan Idaho isn’t a hero because the audience reacted favorably to him. His story may be thousands of pages and many lives long, but nothing about it is crowd-sourced. This is the unflinching vision of one man from the 1960s on Earth who will never come again – his remarkable, poetic renderings of the royal drama on a distant desert planet in the unforeseeable future. Changing everything around us, he attempts like few masters to shine light on what is eternal in the human condition.

The sleeper will awaken.

And the spice will flow.

“Make no heroes,” my father said.

Ghanima Atreides

All images and quotes are used with respect to their respective creators. Anyone looking to have their work credited or removed need only contact the author.

Buy Joshua a Coffee!

Like what we’re doing here? We accept tips. Just a small contribution says you believe in what we have to say at Arch + Gravity, Ink Tone and The Shadow Lab. As a bonus we’ll add you to the list to receive updates on new projects as they evolve.